ISO

ISO is one of the three corners of the exposure triangle. Unlike shutter speed and aperture, ISO doesn’t control how much light gets onto your recording surface (film or chip). Instead, it’s a measure of how sensitive your surface is to light.

If you’re using film, sensitivity is a pain to change because you have to remove the film you’re using and replace it with a new roll with a different ISO rating. Digital chip sensitivity can be reset whenever you want to change it, but in general you’re better off controlling your exposure by manipulating your shutter and aperture.

If nothing else, shutter and f-stop are usually easier to change than ISO. That’s partially a camera manufacturer “old school” carry-over from the film days when you couldn’t change ISO on the fly. But it’s also an image quality issue, as you’ll see in this example.

iPhone 5s

For this shoot I’ve deliberately made things hard. The snapshot I look with my phone doesn’t do justice to the full darkness of the room. To get a photo of my old Kendo helmet lit only by a dim lamp, I set my camera on a tripod and used a 28-200mm lens zoomed to 170mm. I set the aperture to f/11 and balanced the shutter speed and ISO to get the proper exposure.

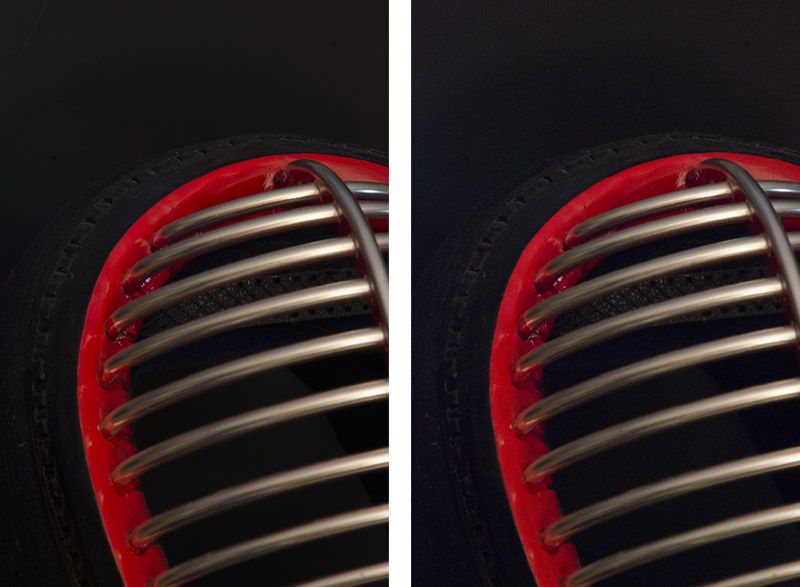

25 sec, ISO 100

1/2.5, ISO 6400

They look pretty much the same, don’t they? They’re at the same EV, the shutter speed counter-balancing the change in the ISO. The 1/2.5 shutter speed isn’t super, but it’s a lot closer to practical than the 25 seconds it took for the lower ISO. So why not crank up the ISO every time you’re in a low light situation?

Let’s take a closer look.

25 sec, ISO 100

1/2.5, ISO 6400

The higher ISO makes the photo look grainy. It can also cause color distortion (though I lucked out on that count here). So the trade-off here is light sensitivity versus image quality.

This was one of my great frustrations when I first made the switch from film to digital. Higher ISO film is more light sensitive because the grains of photosensitive chemicals in it are bigger. Thus one would expect a grainier look from high ISO film. But the pixels on a imaging chip are the same size no matter how high the ISO is set. So why do the pictures still look grainy? Was that something camera manufacturers assumed we wanted? Because not so much.

Finally I got to have a chat with a camera tech specialist who explained it to me. The chip becomes more light sensitive when the electrical current running through it is increased. Unfortunately, the stronger current causes more “misfires,” errors in the data that lead to the grainy appearance.

Oh, and in case you were curious, ISO stands for International Organization for Standardization, the organization that sets internatonal standards for many things, including photographic light sensitivity. If you have a camera manufactured before the mid 1980s, the setting you need to adjust to tell the camera what kind of film you just loaded may be labeled ASA. That was the American Standards Association, creator of the standard that was adopted by the ISO.

For more examples of how ISO affects light and image quality, have a look at these entries in The Photographer’s Sketchbook blog.

You’ll also find plenty of links to further information about ISO on the “Camera Controls” board on Pinterest.