Communication in its most basic form is the art, craft and science of moving information from one mind to another. At a primitive level, the ability to get someone else to understand “Hey, we’re about to be attacked by a cave bear” is a simple matter of survival. As the spoken word became more sophisticated, we were able to add persuasion (“Remember, only you can prevent cave bear attacks”) and entertainment (“Listen to my story about how our Great Ancestor defeated a cave bear”). But at its heart, information is still the key.

In the mass media, the purest form of information exchange takes the form of journalism. No matter what medium they work in, reporters are dedicated to finding out about all the important doings in the world, creating news about them and getting it to the public. In the 21st century we tend to worry a little more about things like crooked politicians, economic downturns and celebrity rehab than we do about cave bears. But the underlying need is still the same.

Reporting

Reporting is journalism in its most basic form, stories designed to provide newsworthy information to their readers. And of all the words in that last sentence, “newsworthy” is the key.

Newsworthy information meets three standards: it’s relevant, useful and interesting. “Relevant” means that the subject of the story is connected to its readers in some way. Thus a story about a plane crash is likely to be relevant to more readers than a story about what you had for breakfast this morning. Likewise a story about a plane crash at an airport in your city would be more relevant to you than a story about a plane crash halfway around the world.

Relevance also helps make a story more useful, providing information that readers can actually do something with. By this standard, a story about a series of car thefts in your area is more newsworthy than a story about a celebrity in California busted for DUI. The car theft piece lets you know that it might be a good idea to get a car alarm installed (or if you already have one, to be careful to turn it on at night).

And yet stories that aren’t particularly relevant or useful to us get reported all the time, at least in part because the third standard – whether or not a story is interesting – looms large in 21st century news coverage. Even though we can’t make much practical use of celebrity gossip and the like, we do seem to be endlessly fascinated by it.

The general term “reporting” covers a wide range of writing styles, from short, basic news stories to in-depth feature pieces, from simple “just the facts” coverage to more complex styles, some of which blur the line between news reporting and other kinds of writing such as opinion and even fiction.

Photojournalism

As reporting is to words, so photojournalism is to pictures. Photojournalists take pictures that tell newsworthy stories.

The craft requires mastery of two different disciplines, both the science of journalism and the art of photography. Successful photojournalists have to master their cameras the same as any other photographer, but they must also learn to look for scenes that tell newsworthy stories.

Indeed, being in the right place at the right time is just as important as having the skill and training for the job. A photo of a fireman holding a baby in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 stirred the emotions of millions even though it was taken not by a trained photographer but by someone who happened to be at the scene and have a camera on him. However, talent and training vastly improve your chances of being ready when the opportunity for the “perfect shot” comes up.

Good photojournalists are powerful communicators. Think about the big moments that you’ve learned about in books or that have occurred in your life. For each event, what do you remember best: a carefully-worded story about it, or a picture? If nothing else, good photos serve as “ads” for associated news reports, whetting our curiosity and getting us to “read all about it.”

Even in the 21st century with all its moving, talking images, plain old still photography is still a powerful form of news coverage.

Opinion

The main function of a newspaper is – obviously – news. But newspapers and news magazines also feature other kinds of content as well. The “inside pages” often include a mix of news, sports, cartoons, crosswords, horoscopes, and of course lots and lots of ads.

One of the strangest parts of the newspaper is the Opinion section, “strange” because if news is supposed to be an unbiased presentation of facts then opinion is in many ways the exact opposite. Writing on the Opinion page is designed to persuade readers to adopt a particular point of view or system of belief.

Traditionally, journalistic opinion writing is divided into two types. Editorials follow a fairly strict format. A good editorial starts by identifying a problem. Then the writer explores differing points of view on the subject. And the piece finishes up by proposing a solution to the problem.

Columns tend to be more free-form. However, they still follow the newspaper’s established writing style and content policy. They also tend to be written by “regulars,” columnists whose work appears on a schedule rather than just whenever a thought pops into the writer’s head. Thus professional opinion writing remains an art distinct from blogging and other styles better suited to social media.

Broadcast News

By the time broadcasting thoroughly captured the public’s attention – radio in the 1930s and television in the 1950s – print journalism’s modern standard was already well established. In the new media, however, reporting could have followed either standard of accurate, honest coverage used by newspapers or it could have reverted to the sensationalized journalism of years past.

CBS did a great deal to establish a high standard of professionalism for broadcast news. The “Tiffany Network” excelled not only at quality programming in general but also at supplying the public with accurate news from across the nation and across the world (even when doing so wasn’t the cheapest option available).

The most prominent faces of this commitment to quality were Edward R. Murrow (famous for his “This Is London” radio broadcasts and his opposition to McCarthyism) and Walter Cronkite.

“Uncle Walter” became the visible symbol for the best in American journalism. When President Kennedy was assassinated, Cronkite choked back his emotion as he broke the news. Throughout the turbulent 60s and early 70s, viewers tuned into the CBS Evening News to listen to Cronkite’s calm, professional coverage. His newscasts became so influential that when he began to express skepticism about the progress of the war in Vietnam, some credited him with playing a major role in the U.S. failure in Southeast Asia.

Cronkite was perhaps the last media figure considered genuinely trustworthy by viewers. Though many news people and news shows – notably CBS’s 60 Minutes – continue to impress the public, no one figure has recently managed to capture viewers’ faith the way “Uncle Walter” did.

The future of TV news

In 1976 Sidney Lumet directed Network, a movie based on a novel by Paddy Chayefsky. Set in the news division of UBS, a fictional TV network, the movie tells the story of a news anchor who goes insane on the air. Naturally the news director fires him, but then network executives intervene when it turns out the crazy man is extremely popular with audiences.

At the time the plot was a comical farce. No respectable broadcast news operation would ever compromise its ability to inform just for the sake of using entertainment to gather bigger ratings.

In the 21st century, however, Network seems less like a farce and more like a documentary. As networks increase their emphasis on higher profits, expensive operations such as news divisions have suffered cutbacks that have limited their ability to perform up to the standards of years past. Audiences are at least partly to blame, often all too willing to settle for entertaining fluff rather than insisting on professional news coverage.

That isn’t to say that TV news is a “vast wasteland” of cheap garbage. However, dedicated news professionals will have to remain vigilant against increasing pressure to cut costs and increase viewership at the expense of quality.

The Fourth Estate

Governments with roots in Europe somehow just seem to naturally get divided up into three “estates.” The specifics vary from place to place. Sometimes its royalty, nobility and clergy. In others it’s royalty, nobility and commons. In the United States – where we’re not so much with the royalty – we divide things into legislative, executive and judicial branches.

But often another party enters the game, a “fourth estate” that isn’t a literal part of government but nonetheless serves as a check on the power of the official three. The news media are potentially perfect for this role.

Investigative journalism is the fourth estate at its most effective. Rather than merely take the word of those in government, big business and other seats of power, investigative reporters dig behind the scenes. By uncovering the things those in power don’t want disclosed, good reporters empower their readers to make informed decisions about whom to vote for, whom to do business with, and generally how to lead a less zombie-like life.

You’ve already encountered several examples of great investigative journalism, from the Muckrakers to Watergate.

Information access

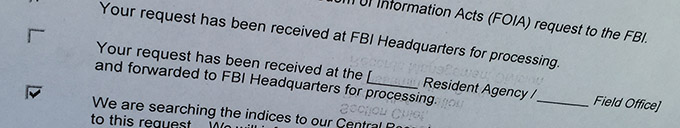

Investigative reporting depends on access to information. Those in power don’t just voluntarily give up their secrets. So the y must be forced either by operation of law or journalistic craft.

On the legal front, open access to information held by the government is required in many situations. At the federal level, the Freedom of Information Act defines what the government must disclose in response to a written request. States also have access laws such as the Kansas Open Records Act and the Kansas Open Meetings Act.

However, some material isn’t covered by the acts. In some cases, such as legitimate protections for national security, may require even the most zealous reporter to know when to back off a little. In other cases the government may use what seems like a legitimate reason to hide information that should be disclosed, requiring a good reporter to keep digging. Conclusion: it isn’t always easy even for a good reporter to know exactly what to do.

Outside the halls of government, information access can be a far trickier business. Except in limited circumstances, corporations are entitled to keep information private and are under no obligation to tell reporters anything. In this realm, use of confidential sources – whistleblowers and other “insiders” – is far more common.

Accuracy and honesty

Whether it’s a huge, investigative story that takes months to prepare or a simple report about a Board of Trustees meeting that takes 20 minutes to write, good journalism depends on two factors: accuracy and honesty.

Accuracy is easy. Or to be more precise, accuracy may require a lot of work, but it’s usually a straightforward business. If a party guest breaks a millionaire’s $500,000 vase, you need to verify that the vase is worth $500k. If you do a couple of interviews, ask an appraiser and get different answers, then your story should accurately report that the millionaire says the vase was worth $500k, the guest thinks it was actually worth only $50,000 and an outside expert puts the figure closer to $100,000.

Honesty is a more philosophical matter. In the modern style of journalism, reporters make their stories honest by remaining neutral and giving equal weight to all sides of an issue. But some journalists are beginning to challenge the requirement for detachment, arguing that reporters could be more honest if they were allowed to get more directly involved in the issues they write about.

Ethical challenges

Professional ethics in the media realms take two forms: general principles and specific rules. The code of the Society of Professional Journalists makes a good case study, because the society admits both print and broadcast journalists and thus has rules that don’t depend on one particular medium or media outlet.

The society encourages members to “seek truth and report it,” “minimize harm,” “act independently” and “be accountable.” Each general principle is a goal that can be realized by obeying specific restrictions. For example, in order to “act independently” a journalist must avoid conflicts of interest, disclose unavoidable conflicts, refuse gifts and so on.

Ethics documents such as the SPJ’s code often serve as the basis for specific rules governing the conduct of employees of specific newspapers, TV stations and so on. Even relatively small student newspapers such as The Advocate – KCKCC’s former school newspaper – have a Code of Conduct that places limits on its staff. The Advocate’s rules were inspired by the codes of the SPJ, the Associated Collegiate Press, and several other professional and student publications.

Journalists in jeopardy

In the United States, the First Amendment of the Constitution protects journalists from direct government censorship. We also enjoy the same protections as everyone else from illegal search and seizure, false imprisonment and the like.

In the real world, however, things aren’t always so simple and clear. During the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011, police in some areas established a pattern of arresting not only protesters engaged in illegal conduct but also reporters who were on the scene attempting to cover the story.

Sadly, the government isn’t the only potential source of threats against reporters. Unscrupulous businesspeople and members of organized crime can be particularly aggressive when protecting their operations from outside interference no matter what the source. Though this isn’t a common occurrence, journalists have been threatened, attacked and even killed in the course of working on stories.

Fake news

The phrase “fake news” is an oxymoron. Accurate, honest reporting is by definition not fake. When journalists make mistakes, they must correct all inaccuracies in their work. And until recently, dishonest articles and broadcasts were simply called lies.

But the phrase doesn’t really criticize the accuracy or the honesty of a story. It tends to be used to describe anything the speaker disagrees with or finds inconvenient to acknowledge. It steers discussion of public affairs away from legitimate debate and turns the marketplace of ideas into a pointless, childish bicker fest.

The only way to break out of the cycle of constant bickering about the news is for readers and viewers to get enough information to judge the accuracy and honesty of stories for themselves. That’s unfortunate, because many people don’t have the time, energy or resources to test the reliability of what they read. And a few sad people – on both sides of the political spectrum – don’t care about the news value of anything inconsistent with their personal beliefs.

But it’s also fortunate in a way, because news should never be taken for granted. People should question what they see, hear and read. And if we happen to agree with the news, then we should question it all the harder to make absolutely sure that we’re actually right.

Backpack journalism

In the 20th century, journalism was a divided profession. Writers worked for newspapers, and when they covered stories with some potential visual appeal they usually took a photographer along with them. Newspaper folk seldom if ever worked with audio (the domain of radio reporters) or video (the realm of TV journalists). TV news coverage was particularly expensive, requiring not only a reporter but also a cameraperson, a sound person, and a tape editor back at the station and a producer to keep everything running smoothly.

The 21st century is a different place. Thanks to improvements in media technology, you now no longer need to be a highly trained expert just to operate a video camera or edit a TV news story together. Thus a person who has journalism training and basic audio and video production skills is a much more valuable employee than someone who can’t meet all the demands of media convergence.

This new style of news coverage has a name: “backpack journalism.” The term refers to the ability to fit everything you need to fully cover a story – laptop, still camera, video camera and audio recorder – into a small, easy to carry container such as a backpack. With just a few simple pieces of equipment, one person can research a story, record interviews, shoot stills and video, write the story, edit audio and video, save everything in multiple formats and upload it to her employer.

Who is a journalist?

In the United States, it’s fairly easy to tell the difference between someone who isn’t a doctor and someone who is. Gone are the days when a quack like John R. Brinkley could get a medical license and set up a legitimate practice. In order to earn the right to call yourself a doctor, you have to be admitted to med school, pass your classes, graduate from med school, pass a standardized exam and then go through an extended program of internships in order to prepare you to practice on your own. If you don’t meet the requirements, you can’t legally call yourself a medical doctor.

Journalists are a somewhat different matter. Though reporters are professionals just like doctors and lawyers, there’s no specific educational requirement or mandatory exam that has to be passed before a person can start work as a journalist. That’s thanks at least in part to the First Amendment, which protects the freedom of the press from government interference.

Generally this freedom is a great thing. But in the 21st century, new media are starting to blur the line between professionals, amateurs and “journalist-like objects.” On the web anyone can have potential access to the same readers that professional news outlets are trying to reach. A scandal sheet such as The Drudge Report has a URL just like The Wall Street Journal does.

Professional news organizations are sometimes their own worst enemies in the struggle to compete with non-professionals. Increasing corporate control and a creeping emphasis on entertaining, inoffensive coverage is eroding some readers’ confidence in the reliability of the traditional press. This erosion is helping to build markets for alternative voices. Some of these are better than the mainstream media, but others are far, far worse.

Thus readers have to exercise caution when trying to decide whom to accept as a journalist and whom to reject as something else. The difference isn’t as easily apparent as it once was.

The “post-journalism world”

Journalism is in a state of change. Anyone who believes that newspapers can continue to rely on the profitability of their “dead tree” copies or that broadcast networks are still as strongly committed to good reporting as they were back in the 60s isn’t paying enough attention to current trends.

But change is one of the few constants in the universe, and it affects every industry in one way or another. In the 19th century, horses were the best way to get from one place to another. But then change came. Companies that saw themselves as being in the horse business swiftly found themselves out of business. But companies that saw themselves as being in the transportation business were able to adapt and thrive in a new world of trains, cars and airplanes.

Nor have the media been immune to change. In the music business, cassettes replaced reel-to-reel and eight-track tapes. CDs replaced LPs. And then MP3 downloads set the entire industry on its ear. But no matter how easy it was to imagine a “post-eight-track world” or a “post-LP world,” nobody was ever foolish enough to suggest that we were moving to a “post-music world.”

And yet current shake-ups in the journalism industries have prompted some critics to begin envisioning a “post-journalism world.” Those of us who grew up with newspapers and love their traditional look and feel must nonetheless admit that a “post-newspaper world” will most likely be upon us before we know it. But a media marketplace where people seek good reporting online is a far different place from a world where people don’t want to read, hear or see the news at all anymore.

If I had an absolute answer to the question “what form will journalism take in the 21st century?” I’d probably be making more money than I am now. But I’m reasonably sure that it will transform rather than disappear.

I must admit, however, that my opinion on the subject is colored by my inability to imagine how the United States would function in the absence of people who care about their society and thirst for information about the world around them. I hope we never find out what a “post-journalism world” might look like, because I strongly suspect that it would also be a “post-intelligence world and a “post-democracy world” as well.