The magazine industry provides an excellent series of lessons about how survival goes not necessarily to the fittest individual but to the group best able to adapt to change. Several times over its long history, the business has made major changes in the way it does business in order to survive the end of some reader demands and take advantage of new opportunities.

Originally, magazines were nothing but reprints of articles collected from other sources. Indeed, the term “magazine” was borrowed from the building in forts where ammunition, gunpowder and other supplies were stored. Once they came into their own as an independent medium, magazines’ history is a constant dance of finding new ways to appeal to audiences.

This chapter also considers the orphan stepchild of the print media: comic books. Early in their history, comics would have been a subsection of Newspapers. Decades later, new “graphic novels”– which could be a subsection of Books – targeted adult readers. But when comics first started to appear under their own covers, they were serial periodicals much like many “mainstream” magazines. The periodical publishing strategy continues to dominate this corner of the industry, carving it a niche in this chapter.

America’s First National Mass Medium

When the United States first came into being, first as a loose collection of English colonies and then as a nation in its own right, the literate members of this new land created a high demand for print media. Of course at the time – the 17th and 18th centuries – only three media existed: books, newspapers and magazines.

Books were popular, but they tended to be printed by long-established publishers in Europe and then shipped to America for sale. To be sure, some books were printed on the western shores of the Atlantic. In particular, political pamphlets – the smaller cousins of books – were common in the colonies, serving as one of the major causes of the American Revolution. But for the most part the book business was a matter of European imports.

At the same time newspapers were flourishing. Every good-sized city had at least one daily news source, and residents of larger cities such as Philadelphia had several newspapers to choose from. But newspapers were local, then as now designed primarily for readers in the cities of publication.

Even if a newspaper had wanted to target a national audience, distribution speeds would have been an impossible hurdle to jump. News travelled only as fast as physical transportation could carry it. So by the time a newspaper could travel between distant spots – say from Boston to Atlanta – via horse-drawn wagons on rough roads or on ships that depended on the wind for power, the news would be days or even weeks out of date.

Magazines, on the other hand, were perfectly positioned to take advantage of a new sense of America as one nation rather than as divided colonies. Magazine editors could comb through local newspapers and select only those stories that were likely to be of interest to readers in other places and could stay “fresh” for the time it took to get there.

Thus magazines were a big factor in the creation of a home-grown media market in the United States, helping to promote literacy and nationalism at the beginning of the “American experiment.”

The Birth of Photojournalism

In the late 1830s, inventors figured out how to make photography work. For the first time people could use a combination of chemistry and mechanics to record images of the world around them rather than relying on writers’ descriptions or artists’ interpretations. Early experiments were mostly portraits, landscapes and other artistic subjects. But photographers such as Carol Szathmari and Matthew Brady soon realized the new technology’s potential to bring influential images from newsworthy events in distant locations. Brady’s photographs of the Civil War are legendary for recording the horrors of battle with a force no written description could equal.

It took several more years to develop the halftone printing techniques necessary to include photos in mass-produced publications. In the meantime, however, many magazines used photographs as the basis for engravings, black and white drawings that were easier to print using traditional methods. By the end of the 19th century many magazines and newspapers regularly printed actual photographs rather than photo-based drawings.

Unlike newspapers – which had to be produced quickly using cheap paper – many magazine publishers took longer to print and used expensive, glossy paper that did a superior job of reproducing photos. By the 1950s several magazines – including Life, Look, Sports Illustrated and National Geographic – built substantial readerships based in large part on their use of high-quality photojournalism.

Photos do more than just increase a magazine’s appeal to semi-literate audiences. The sense that “pictures don’t lie” lends tremendous authority to photojournalism. In particular, news of unfamiliar, unpleasant subjects such as combat becomes more immediate when delivered via pictures. For example, Eddie Adams’s iconic photographs of the Vietnam conflict did a lot to influence public opinion about the role of the United States in Southeast Asia.

Even in the video-intensive media markets of the 21st century, carefully crafted still images still exert a big influence on readers.

The Death of Life

Life began life in the 19th century as a general interest humor publication. But it rose to national fame in 1936 when Time publisher Henry Luce bought it and switched the emphasis from humor to photography. In short order the magazine established a solid reputation for bringing images from all over the world into America’s living rooms once a week.

Though the magazine contained some text (including stories by Ernest Hemingway and memoirs from prominent politicians such as Harry Truman and Winston Churchill), the main emphasis was on pictures. The approach proved instantly popular with the public. The first issue of the reworked Life sold nearly 400,000 copies, and within four months circulation topped a million. The publication’s popularity helped get Life staffers access to everything from movie stars to combat zones.

Then in the 1950s and 60s the media landscape changed radically. Even well-established, popular media such as Life faced new competition from television. Before long the “box” started cutting into Life’s business, bringing photojournalism into homes without charging a subscription fee or making consumers wait for a week for the next issue to arrive.

Most specialized magazines managed to survive competition from television, because they gave readers information not covered by TV news broadcasts. But general interest publications such as Life and its biggest imitator Look took the hit solidly. By the early 1970s both magazines were out of business. Time Warner – Life’s owner – has since made three or four attempts to revive it, but none have approached the level of success and influence it had in its heyday.

William Gaines

In 1947 Bill Gaines was fresh out of the Army and studying chemistry at NYU, intending to become a teacher after graduation. But then his father was killed in a boating accident, and Gaines suddenly found himself in charge of the family business, EC (which stood for both Educational Comics and Entertaining Comics).

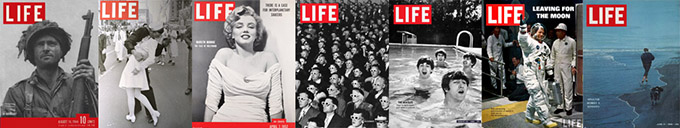

When he first took over, EC was best known for kid-friendly comic adaptations of stories from the Bible. But Gaines swiftly expanded the publisher’s offerings and its audience by introducing new titles aimed at non-juvenile readers. The most famous of these new comics were horror comics, particularly Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror. Other offerings included comics specializing in science fiction (Weird Science), action (Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat) and crime (Crime SuspenStories and Shock SuspenStories).

This new trend at EC included material that was clearly unsuitable for kids, especially graphic treatments of violence and torture. They also took on topics such as racism, which was considered too controversial even for many mainstream magazines designed for grown-ups.

Needless to say, EC became the bête noire of the comic book censorship movement. Gaines didn’t do himself many favors by appearing before a Senate subcommittee and testifying frankly that the principles of free speech and free market competition should control what could and could not be published in comics. However right he may have been, his testimony made him an easy target for pro-censorship forces.

After the Comics Magazine Association of America essentially ran EC out of business, Gaines rebuilt with his one surviving title: Mad. Because this humor publication was technically a magazine rather than a comic book, it wasn’t subject to the CCA code. Gaines ran Mad according to his own standards rather than strictly with profit in mind, For example, he once flew the magazine’s entire staff to Haiti to greet the island nation’s single Mad subscriber. When the bewildered man’s neighbor decided to subscribe, Gaines declared the trip a financial success based on the fact that Haitian subscriptions had doubled.

Despite his eccentric leadership, Mad was a financial success. The publication continues to flourish decades after Gaines’s death in 1992.

Martha Stewart

By many standards, Martha Stewart leads the perfect life. Despite a few bumps in the road along the way, she sits atop one of the world’s most successful multimedia empires, a series of ventures all dedicated to helping people lead a more Martha-Stewart-esque existence.

Stewart’s connection with the media began in 1982, when her catering business served food at a book release party hosted by her husband Andrew, then president of the Harry N. Abrams publishing company. At the party, Stewart met Alan Mirken, head of Crown Publishing Group. Impressed with her catering skills, Mirken hired Stewart to write a cookbook with recipes from her service and photos from some of the high-class parties she’d catered.

The book – Entertaining – was a big hit, followed by a series of likewise-successful books on cooking, entertaining and homemaking. Thanks to the books and to appearances on many talk shows, Stewart cemented her reputation as the doyen of gracious living.

In 1990 she signed a deal with Time Warner to produce Martha Stewart Living, a monthly magazine devoted to her areas of expertise. The magazine was another runaway hit, reaching a high-water-mark of two million copies per issue. It also became the centerpiece of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, a corporation that consolidated the magazine, her TV show, her books and several merchandising ventures into one centrally controlled enterprise. The company now markets just about everything from bath towels to wine to real estate.

Raking the Muck

One of the nice things about owning a monopoly in a business that caters to an inelastic demand is that you don’t fundamentally have to care about anything. Do you charge way too much for a shoddy product? Who cares! If nobody can buy the product from anybody but you, then everyone has to do business on whatever terms you set. Changing the balance of power in such a relationship requires a monumental public backlash against your bad business practices.

Unfortunately for the trusts that controlled American industry at the end of the 19th century, just such a backlash was in the offing. Theodore Roosevelt was elected to the White House thanks in part to his promises to do something about the monopoly problem. However, Roosevelt wasn’t a naïve fool. He knew that it would be hard to get anti-trust laws passed by a Congress heavily influenced by the trusts’ money.

So he turned to the media, encouraging a trend in reporting that he dubbed “muckraking.” This new breed of journalist was eager to take on the trusts, exposing corruption and building public outrage against the system. The most famous single example of muckraking is Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, a book exposing unsafe working conditions and disgusting food safety problems in the meat packing industry.

But magazines were the main muckraking medium. McClure’s magazine led the way, publishing legendary criticisms of trust abuses from the coal mining industry to Standard Oil. Cosmopolitan (yes, Cosmo!) was anther great source of stories, even daring to expose corruption in the Senate itself.

The outcry generated by these articles led to a number of reforms, such as the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and later the creation of laws sharply restricting the use of child labor. Many of the protections first created a century ago are still in place today.

Cover art

In the realm of self-promotion, magazines have one big edge on newspapers: cover art. Traditionally, newspapers treat their outside (front) page as another place to put news stories. Magazines, on the other hand, have a tradition dating back more than a century of decorating their covers with art of one kind or another.

When the cover art practice first began, pictures often had no direct connection to the stories inside. They were selected simply to create a positive impression on readers and increase sales. Often the pictures were of idealized women, giving rise to some of the industry’s first forays into profit-oriented sexism.

Later of course the trend shifted to cover art with some kind of direct connection to the magazine’s contents. Whether it was a concrete connection – such as a National Geographic photo from one of the locations covered in the issue – or merely fanciful – such as an airbrushed painting of a “two-fisted” he-man doing battle with a crocodile (loosely tied to a travelogue about the Nile inside) – the tie-in tradition was established.

This changed the relationship between newsworthiness and marketing. Newspaper editors determine what stories to put “up front” based on how important they are to readers. Their colleagues who work for magazines must determine not only which stories are most important to readers but also which ones are accompanied by the best graphics.

Targeting Readers

As with narrowcasting in the cable television business, magazines tend to live and die based on their abilities to target specific audiences. Thus the industry can be divided up into many subsections. The American Society of Magazine Editors compiles statistics based on lists of hundreds of different publication categories, ranging from broad groups such as “society” to specific professions (“welding”) or interests (“folklore,” “dance” and “cats”).

With all those categories – many of which cover dozens of publications – the full gamut of the magazine business includes far too many titles to stock on the shelves of even the largest bookstores. So selling magazines is a complicated mix of point-of-purchase and subscription sales.

To make matters even more complex, many magazines produce regional editions. These publications cater to a nation-wide audience but also generate content aimed at readers in specific areas. For example, a national news magazine such as Newsweek prints many stories of interest to readers all across the United States. But it also generates a few that appeal to more limited audiences in the Northeast, Midwest, South and West.

Counting Readers

Counting readers in the magazine business works pretty much the same as it does for newspapers. It’s even done by the same company, the Audit Bureau of Circulations.

However, magazines are treated slightly differently. They have longer message lives (usually measured in weeks or months rather than hours), and thus they tend to have longer pass-along rates. Using my household as an example, a newspaper’s pass-along would usually be two (my wife and me). Depending on its subject, however, a magazine might get passed along to four or five people depending on how many of my friends and extended family were interested in the topic it covered. Pass-along would be even higher for a magazine sitting in the waiting room of a dentist’s office, which might potentially have dozens of readers.

Reader counts are particularly important to a subsection of the industry: controlled circulation magazines. These publications are supplied to readers free of charge, a marketing scheme made possible by extreme specialization. For example, imagine you were publishing Blood Analysis Quarterly, a magazine for people who work in the blood analysis business. Your magazine is of such narrow interest that you won’t get much directly from your highly limited audience. But as just about all your readers are potential buyers for blood analysis equipment, which makes your magazine appeal strongly to the companies that sell analysis technology. Because companies with ad dollars want to reach your specific readers, you can charge so much for ads that you don’t have to charge your readers for subscriptions. And giving your magazine away for free to anyone in the target audience increases your circulation. It’s a win-win.

Magazine Advertising

Like newspapers, magazines sell advertising based on the size of the ad and where it’s placed in the publication. One of the most valuable spots in a saddle-stitched (stapled across the fold) magazine is the center spread, the middle of the copy where an ad can stretch across two full pages without losing anything in the binding. The back cover is also prime “real estate,” because a magazine left lying around face down will show the back cover ad to anyone who happens by.

Some magazines also engage in the annoying practice of packing a ton of ads between the cover and the table of contents. This requires readers to flip through page after page of ads in order to figure out how to find the articles they want to read. On one hand, this gets people to look at the ads. However, it may associate those ads with feelings of frustration.

And like the editorial (articles, photos and the like) side, advertising can be customized by geographical region. So the owner of a chain of gourmet grocery stores in the Midwest might be able to buy an ad in a national gourmet magazine that would only appear in the region where her stores are located, thus saving her money and targeting her ad only at readers who stand a chance of becoming her customers. Magazine editions that tailor their advertising in this manner are called split run.

Freelancing

More and more, the magazine industry relies on freelancers for content. Freelancing is sort of a hybrid of working for a company and working for yourself. You’ll agree with an editor about what you’re going to work on (though the original idea might start with either you or the magazine). You’ll also agree about what you’re going to get paid and when you need to have your story done.

For some people, freelancing is the best of all possible worlds. It’s like having a regular job in that you work on a specific task and you get paid when it’s done. But for the most part you can set your own hours and decide for yourself whether or not you want to work on a particular story.

On the other hand, this kind of work isn’t for everyone. Some people find it hard to stay motivated without the structure of a “day job.” And depending on where you are in life, things like employer-funded health insurance and a retirement plan may mean more to you than the footloose life of the freelancer.

Starting a New Title

Two or three times I’ve been called upon to assist someone trying to start a new magazine (note the emphasis on the word “trying”). Advances in desktop publishing technology have made this somewhat more feasible than it would have been in the past. But the basic ability to create magazine layouts still leaves a lot of work yet to do.

For starters, you have to have content. Though it might be tempting to try to generate all the photos and articles yourself, that isn’t a realistic approach. You’ll need a staff of writers (or at least a set of solid freelancers) before you’ll be able to generate enough content to keep publishing on a regular basis.

Eventually you’ll also have to deal with the catch 22 of distribution and ad sales. In order to get the money to actually print and distribute your magazine, you’ll need ad revenue. But it can be hard to impress advertisers that their ads will actually be seen by readers until you’ve actually started printing and know for certain that people want to read what you produce.

Thus my first advice for anyone thinking about starting a magazine is to begin with a web site first. A web presence is cheaper than even the smallest run of a printed publication. It will also give you the chance to determine if you have the dedication and support you’ll need for a printed magazine. And you can use the web to start building interest in your future “dead tree” publication.

Image Editing – How Far Is Too Far?

One of the marvels of the desktop publishing revolution is the increasing ease and quality of digital image retouching. Applications such as Photoshop make it possible even for beginners to make difficult-to-detect changes in photographs.

The ethical rules of photojournalism sharply restrict photo alteration. Photographers and editors can crop the edges of pictures as long as the deletions don’t alter the meaning of the photo (cutting out a key person or other important element). Some adjustments of brightness and contrast can also be made in order to get the picture to look in print as the scene originally appeared to the photographer’s eye. Beyond that, tampering with images is strictly forbidden. Photojournalists have been fired for making even relatively innocent changes.

Magazines that don’t specialize in news may have more lax standards about photo alteration. Indeed, in the fashion industry it’s so expected that it’s practically required. Photographers routinely correct for lighting and makeup problems.

However, sometimes even ad and fashion retouching push the limits when they change a model’s physical characteristics. Making women look thinner is a fairly routine practice, but it draws criticism from those who argue that the result creates unrealistic expectations about body image. Questions of racism also sometimes arise, such as when a L’Oreal ad’s creators significantly lightened Beyonce Knowles’s skin tone.

The Comics Code

In 1954 a strong anti-comic-book movement was afoot in the United States. Spurred by Seduction of the Innocent by Fredric Wertham, the movement turned the early 50s spirit of vicious intolerance onto comics, accusing even relatively innocent titles such as Superman of corrupting America’s youth and turning young boys into criminals and perverts.

Comics publishers started to take the threat particularly seriously when the U.S. Senate’s Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency convened a hearing to consider the subject. The Senate opted not to act after the industry took steps to deal with some of the concerns on its own.

Thus the Comics Magazine Association of America was born. The association formed the Comics Code Authority to police the comics publishing business. The CCA started with an old, seldom-used code of restrictions that had been created years earlier based on the Hays Code that controlled the movie industry at the time. But then it added new restrictions on elements such as “lurid illustrations” and depictions of vampires, werewolves and other monsters.

These new additions were aimed directly at EC, which had seen considerable success from non-kid-friendly titles. Though EC owner Bill Gaines originally advocated the idea of an industry authority to help ward off government regulation, the mainstream publishers now used the authority to eliminate competition from EC. Comics without the CCA seal of approval on the cover weren’t stocked by retailers. In less than a year all but one of EC’s titles were gone.

Further, once EC was run out of business and public furor about comics died down a bit, the industry returned once again to less restrictive practices. The code was quietly amended to allow publishers to use many of the “shocking” elements that made EC so popular.

How to Build a Nuclear Bomb

Here’s something you may not know about the world’s most dangerous weapon: nuclear bombs are amazingly easy to build. In theory, that is. Most atomic weapons require complex triggering systems and radioactive materials not usually found at your neighborhood Home Depot. Basic bomb design, on the other hand, isn’t all that complicated.

The interesting question, then, is whether nuclear bomb designs are secret. When Congress created the Atomic Energy Commission, it gave the agency the authority to prevent public disclosure of information about bomb making. As early as 1950, the commission asked Scientific American not to publish an article it felt disclosed too much about the physics of nuclear explosions.

Then in 1979 The Progressive, a magazine known for printing articles critical of the government, prepared to publish an article by freelance reporter Howard Morland that revealed how H-bombs were made. Morland researched his article using material already available to the public. With the knowledge and permission of the Department of Energy (the successor to the AEC), he toured some nuclear weapons production centers. However, at no time did he have access to classified documents.

Nonetheless, when the DOE learned that The Progressive was getting ready to publish the article, it went to a federal judge and asked for an injunction preventing the magazine from going to press. Based on the government’s authority under the Atomic Energy Act, the judge granted the government’s request.

The block was no small matter. As discussed in the Newspapers chapter, prior restraints cut to the heart of the First Amendment’s protection for freedom of the press. But before the court’s decision could be appealed, another magazine picked up the same basic facts and printed them before the DOE could learn of it and go after another injunction. The proverbial cat was now out of the bag. The court determined that there was now no longer any point behind the ban and lifted its injunction, allowing The Progressive to publish.

Stealing Faces

In some ways, photojournalists have it easier than photographers working in the advertising business. In particular, news photographers don’t need to get consent from the people in their pictures. On the ad side, however, using a person’s name or likeness for a commercial purpose without permission can lead to a lawsuit for appropriation.

For the most part, the distinction is clear. But every once in awhile an odd exception will crop up. In 1975, Sports Illustrated printed an ad for itself. The ad featured several covers from past issues, including one with a photo of Joe Namath, the NFL’s most famous quarterback at the time. Namath sued, claiming that the magazine was using his picture for a commercial purpose without his permission.

The court found that the magazine hadn’t illegally appropriated Namath’s image. The picture was part of a cover, which was a news use. The ad didn’t imply that Namath endorsed the magazine in any way. Thus Sports Illustrated was just showing off a past success in order to lure future readers. No appropriation had taken place.