Film historian Arthur Knight called movies “the liveliest art.” Movies have light and sound. They create an illusion of motion. They feature dialogue and music, plot and character, action, romance, you name it, it’s in a movie somewhere.

Further, there’s just something about seeing a movie in a movie theater. The experience affects us psychologically in ways most other media don’t. I sadly admit that – like many other people – most of my movie consumption is at home rather than at a theater, and even a large, high-def screen isn’t the same as the full theatrical experience. But on the flip side, nobody yaks on a cell phone or aims a laser pointer at the screen in my living room.

Movies are also the most American medium. From the early days of Edison’s studio to Hollywood’s golden age, movies were a huge cultural export from the United States to countries all around the world. Even today American studios tend to dominate the market, though many other nations have their own lively movie industries.

Famous director Cecil B. DeMille sometimes began his movies by delivering a filmed speech before the opening credits. The practice struck me as sort of silly. Nobody came to hear him pontificate. They came to see the story he was about to tell. So in that spirit, let’s dig in.

The Kiss

One of the first movies ever shown caused the movie industry’s first “sex scandal.”

Once the folks on the technical side figured out how to make the medium work, it was up to the early movie producers to come up with something audiences would actually want to watch. Most of the “movies” made at the Edison Studio prior to 1896 were intended only to test the new equipment or study motion from a technical standpoint. Subjects were often nothing more interesting than a technician jumping up and down.

In order to draw actual, paying audiences, the studio turned to that old standby: sex. They hired a couple of well-known stage actors to kiss in front of the camera. In theory this was a film version of the end of The Widow Jones, a stage musical. But of course with only 40 seconds of running time, the movie didn’t amount to much more than a kiss between the two characters.

By our standards, the picture is beyond tame. Indeed, even by 19th century standards it wasn’t all that scandalous, especially compared to the “French postcard” pornography business that would soon spread to the fringes of the new medium. Nonetheless, this simple expression of affection upset many critics who felt the movie business was getting started on the wrong foot. The Kiss produced the first – but sadly not the last – outcry for government censorship of movies.

The Birth of a Nation

In the movies’ early days, audiences were easy to please. “Actuality films” – short clips of trains going by or people walking down the street – were enough to keep people entertained. But as the novelty of the new medium started to wear off, the public needed something better.

In 1914 director D.W. Griffith began shooting what would become known as the world’s first narrative film, the first production to make use of many of the visual storytelling techniques now common in just about every movie ever made. The Birth of a Nation demonstrated what the new medium could really do, helping transform it from a passing fad to an enduring cultural force.

Yet despite the movie’s key role in motion picture history, it’s rarely shown in film studies classes (indeed, I earned a Bachelor’s degree in film without ever seeing it). The problem: overpowering racism. Even by the less sensitive standards of the early 20th century, this picture is way over the top. It tells the story of the “heroic” Ku Klux Klan, bravely defending the flower of white womanhood against predatory black men (played by white actors in blackface) in the wake of the Civil War. The picture is credited with helping to revive the Klan.

Although Griffith’s technical genius was buried under a pile of vile nonsense, the movie was popular with audiences (white audiences, anyway) and many critics. The director went on to make less offensive use of his talents, and other filmmakers used his techniques to create the movies as we know them today.

The Jazz Singer

As we’ll see when we get to the history of movie tech, sound is a tricky business. For the first three decades of their history, movies were “silent.” Many of them were designed to be accompanied by live music from pianos, organs or (in big cities with “movie palaces”) whole orchestras.

In 1927 Warner Bros. came out with the first “talkie,” a feature-length movie with synchronized singing and dialogue. The Jazz Singer used sound recorded on sound discs, which turned projection into a complicated affair requiring skilled technicians in the projection booth. The studio invested heavily in the production, essentially betting the farm that audiences would flock to see this new technological wonder.

The bet paid off. Critics and audiences alike were impressed by the movie. The complexity of the projection process also forced changes in the way movies were distributed to theaters. Most of all, it proved beyond question that “talkies” were a technical and popular success. Though some studios still regarded them as a fad, in reality the age of motion picture sound had begun.

Citizen Kane

Ask a variety of serious film experts to make lists of the best movies ever made, and you’ll get a variety of responses. But one movie makes just about every list.

Director Orson Welles was new to Hollywood in 1939 when he was signed by RKO Pictures. Despite his lack of experience, the studio gave him “final cut,” absolute creative control over the movies he made. With this rare leeway, he made Citizen Kane.

The movie tells the story of Charles Foster Kane, a thinly-disguised fictional version of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst (who we’ll meet again in the newspapers chapter). At the beginning Kane is young and idealistic, but he ends up corrupted by his own wealth and power. Needless to say, Hearst wasn’t exactly flattered by the portrayal. He tried unsuccessfully to get RKO to kill the movie. And his newspapers made no mention of the movie at all, helping to assure that it flopped at the box office when it was released in 1941.

Despite its initial commercial failure, the picture remained popular with critics and academics. Welles’s skillful combination of script, characters and technical innovation made it an excellent example of cinema art. It got a lot more favorable attention in its 1956 rerelease, cementing its place in the history books. It also made Welles responsible for key moments in two different media (we’ll meet him again when we get to the radio chapter).

Rebel Without a Cause

In the 1950s the movie business found itself up against competition from the newly-emerging television industry. TV sets served up the same audiovisual entertainment people used to have to go to movie theaters for, but television did it at home for free. In order to compete, the movies had to do something that television couldn’t (or at least wouldn’t).

One of Hollywood’s new marketing strategies was to provide people with stories too taboo for FCC-regulated, family-friendly TV shows. Mental illness, alcohol and drug abuse, teen rebellion and other scandalous topics helped draw audiences back into theaters. Though many of these pictures are tame by today’s standards, at the time they were groundbreaking stuff (especially from the big Hollywood studios).

Rebel Without a Cause was the most famous and most typical example. James Dean and Natalie Wood headed a cast of teens struggling with drinking, street racing and dysfunctional relationships with their parents. Despite a generally preachy script, the actors manage to create a genuine sense of teenage malaise that caught on with audiences. Box office receipts may also have been boosted a bit by Dean’s death in a car crash less than a month before the movie premiered.

Night of the Living Dead

From its origins in the 1890s, major studios, big corporations that controlled every aspect of the business, dominated the movie industry. Even in the early days, however, independent producers provided the studios with at least a little competition. “Indy” movies didn’t haul in tons of cash the way studio releases did (or at least were designed to do), but then they didn’t cost millions to make, either.

In the 1960s, independent movies began to emerge from the shadow of studio blockbusters. Filmmakers such as George Romero figured out that for a few thousand dollars anyone with a camera could make a movie. Indies couldn’t match Hollywood’s technical quality, and they didn’t feature expensive, big-name stars. On the other hand, directors who weren’t under the studios’ thumb had a lot more creative leeway.

Romero’s Night of the Living Dead is an ideal example of this new movie movement. This black and white tale of zombie mayhem is more than a little rough around the edges. But the script is good, the cast works well, and the production goes farther into horror violence than mainstream movies would have at the time.

The movie sparked an entire sub-genre of sequels and imitators. Romero spent $114,000 to make the movie, and it earned more than $12 million before somebody noticed that the original distributor didn’t include a proper copyright notice, thus placing the movie in the public domain. The picture’s creative and financial success helped prove that people could work outside the system.

Star Wars

Facing ever-increasing competition from television, independent productions and foreign imports, in the 1970s Hollywood studios fell back on their one big advantage: blockbusters. Movies with big stars, huge production budgets and equally huge promotional campaigns were still the sole domain of the corporations who’d been in the business for decades.

In 1975 director Steven Spielberg gave the movie world a taste of the new blockbuster world to come. Jaws wasn’t exactly a cheap production, but it wasn’t a huge investment by studio standards. But it caught on big with audiences, turning huge profits and leaving even some people in Kansas afraid of sharks.

But it was eclipsed just two years later by Star Wars (now known as Star Wars Episode Four: A New Hope). It didn’t cost a fortune to make. It captured the public’s attention in a big way. And it went one step further: in addition to box office receipts, the movie made a ton of money from ancillary merchandise. The Star Wars brand showed up on clothes, toys, lunchboxes, you name it. And of course it spawned a string of sequels. The result went beyond “popular movie” and became a genuine cultural phenomenon.

Do the Right Thing

In the late 1980s, the American dialogue about race had stagnated. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s had lost steam, its leaders assassinated or marginalized. Integration and affirmative action had achieved enough success that many white people began to believe that racism was no longer a problem.

In 1989 director Spike Lee scraped the scab directly off the racism wound with Do the Right Thing. His comic-dramatic tale of racial tension on a hot day in New York City spoke openly and honestly about prejudices that had vastly overstayed their welcome.

It almost goes without saying that some critics reacted strongly against the movie, accusing it of stirring up race hatred and potentially provoking riots. However, others recognized the film’s quality and the importance of its message. Do the Right Thing won several awards and occupies a spot on many “best movies” lists.

W.K.L. Dickson

Though Thomas Edison is often identified as the Father of the Movies, many of the key inventions that made the first motion pictures possible were actually created by Edison’s employee, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. Though Edison worked out some of the electrical details, Dickson was responsible for working out the complicated mechanics of motion picture cameras.

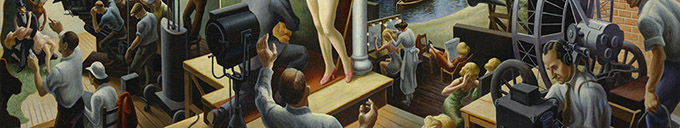

The Edison company set up the world’s first “movie studio” in West Orange, New Jersey, in 1893. Called the Black Maria, it was basically a big box with a large skylight in the top. At the time the sun was the only light source bright enough to expose film fast enough for a movie camera, thus the studio was set up on circular tracks so it could be rotated to follow the sun across the sky.

Of course it wasn’t enough to just shoot a movie. People had to be able to watch it as well. So Dickson developed the Kinetoscope, a box with a small viewing screen in the top. Viewers could stand one-at-a-time next to the box, peer in through the screen and watch short films.

And short means short. The first copyrighted movie was a two-second clip of Edison employee Fred Ott sneezing. Most Kinetoscope films were a bit longer than that, but their length was still limited by the amount of film that could be stuffed into the box.

The Lumiere Brothers

Edison and his staff proved that movies could be made. But their exhibition device, the Kinetoscope, suffered from serious movie length and audience size limitations. On the other side of the Atlantic, however, another pair of inventors were solving the problems that limited Edison’s success.

French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière were the first to figure out the crucial step the movie industry needed to move past the “nerd stage” and become a true mass medium. Rather than stuffing movies into a box, the Lumières invented the movie projector, which they called the Cinématographe. By shining a bright light through film, they got images to project onto a screen. This allowed an entire theater full of people to watch a movie at the same time (rather than the one-at-a-time viewing of the Kintetoscope). And projectors could show as much film as could be run through them (especially if more than one projector was used in series). So movies were no longer limited to short clips.

Shortly thereafter Edison’s team came up with a similar device called the Vitascope, and the movies were finally on their way to becoming a full-fledged mass medium.

Louis B. Mayer

If I had to pick just one person to represent the Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1930s, that person would be Louis B. Mayer. He was the final M in the MGM studio, and he’s most famous for inventing the Hollywood star system.

Born Lazar Meir in Ukraine, his family emigrated to Canada. When Mayer was 19 he moved to Boston, where he purchased and renovated a theater, thus beginning his career in the movie business. After making a chunk of cash by buying the New England exhibition rights to The Birth of a Nation, he moved to California and went into the movie production business.

Meyer recognized the value of marketing movies based on their stars, so he negotiated contracts that kept big-name actors working for MGM rather than whichever studio happened to be paying the most. Thus his stars worked more like employees and less like independent celebrities. He had a reputation as a skilled negotiator, earning him a mixed reputation among the stars who worked for him.

His business model paid off. During the Great Depression, MGM was the only movie studio that consistently paid dividends to its investors. As a result, Meyer became the first person ever to earn an annual salary greater than $1,000,000.

After World War Two, however, his fortunes reversed. The movie industry fell on hard times thanks to competition from television, and MGM stuck to a diet of “wholesome family entertainment” pictures that had trouble competing in the new movie marketplace. Though he had made millions from the business, he wasn’t a major shareholder in the studio. So when it faced financial ruin, the studio fired him.

Sergei Eisenstein

Here’s an experiment you can try on your own: the next time you’re watching a movie, count how long the shots last. When a new shot begins, count the seconds until the movie cuts to a new location or camera angle. For most movies, more often than not you won’t find yourself counting much higher than five.

This wasn’t always the case. In the early days, filmmakers tended to regard themselves as the heirs of the theatre business. Shots were static (the camera didn’t move around a lot) and long, recreating the experience of watching a play.

Then in the 1920s a movement arose in the Soviet Union that took an entirely different approach. These new moviemakers – most prominently director Sergei Eisenstein – regarded cinema as a graphic art. They concentrated not just on the story but how it was visually told. Shots had to flow together when they were edited. Eisenstein’s 1925 silent film The Battleship Potemkin is still used in film schools today to teach editing technique.

His new way of putting movies together greatly strengthened their impact on audiences. Because his most famous work was created under the Soviet system, they’re not only technical textbook examples but also strong pieces of Communist propaganda.

Leni Riefenstahl

Despite considerable talent as a movie director, Leni Riefenstahl’s career was hampered by two things: she was a woman and she worked for the Nazis.

Riefenstahl began her career in Germany making movies about mountain climbing. But after Adolph Hitler saw her work, he invited her to make a movie about the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg in 1934. The resulting documentary – Triumph of the Will – remains one of the most famous propaganda pictures ever made. Large portions of the movie are boring and/or evil speeches by party officials, but the rally overall was designed to be an immense show of Nazi power. The documentary captures the spirit of the event.

Her next feature-length project was a picture about the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Olympia is a landmark moment in the art and science of visual sports coverage. Have you ever seen a sports broadcast in which a camera moves to follow an athlete? Riefenstahl invented that.

Of course when one does brilliant work in the service of something as monstrous as Nazism, it can be a real career killer. Though officially cleared of connection with the Nazis’ crimes against humanity, her involvement with Hitler’s regime dogged her for the rest of her life. It also kept her from receiving the recognition she might otherwise have gotten for success as a movie director, a field still strongly dominated by men.

Gordon Parks

Kansas native Gordon Parks was one of those remarkable people who seem to be good at just about everything he tries. Musician, composer, author, photographer, painter, civil rights activist, and successful at all of it. However, here we’re concerned with his career as a filmmaker.

After serving as a consultant for a series of movies about life in American ghettos, Parks made history by becoming the first black director of a Hollywood movie. The production, The Learning Tree, was based on his autobiographical novel of the same name.

His most famous movie, however, was Shaft. Released in 1971, the picture featured Richard Roundtree as a private detective hired to find the missing daughter of a gangster. The movie was a big hit, thanks in no small part to the soundtrack by Isaac Hayes. It helped usher in the era of “Blaxploitation” movies, productions that rely heavily on 70s era Black stereotypes.

By today’s standards the clothes are outlandish and the dialogue even worse. But at the time, such movies were a big step for Black actors. In this new breed of picture they played action heroes, love interests and many other roles denied them in the butler-and-maid world of traditional Hollywood filmmaking.

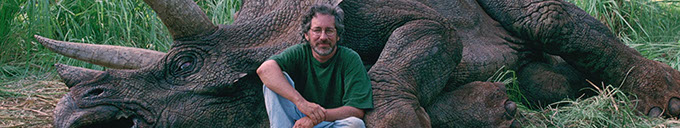

Steven Spielberg

If Louis B. Mayer is the name that comes to mind whenever Hollywood’s Golden Age comes up, then Steven Spielberg gets a similar honor for his role in the current world of Hollywood blockbusters.

Spielberg began his career directing TV shows and relatively small movies. His first big hit was Jaws, which made hundreds of millions of dollars and ushered in the Era of the Blockbuster. His next big hit – Close Encounters of the Third Kind – would most likely have enjoyed a similar level of wild success had it not been overshadowed by Star Wars.

In 1981 he made Raiders of the Lost Ark, the first installment of the successful Indiana Jones franchise. Then in 1982 he created E.T., his single biggest success.

After that he moved away from blockbuster “formula” pictures and into more serious filmmaking with pictures such as The Color Purple and Schindler’s List. Though none of his later movies ever approached the high water mark set by E.T., he still maintains a solid lead as the all-time leading director in box office gross, his nearly $4 billion almost doubling his nearest competitor.

With his earnings he co-founded DreamWorks Pictures in 1994.

Persistence of Vision

Motion pictures don’t actually move. Instead, they’re made up of a long series of still photographs shown in a sequence rapid enough to trick the eye into perceiving motion.

Originally this was a trick used in a kids’ toy called a Zoetrope, which spun around and made the pictures inside look like they were moving. But then photographers such as Eadweard Muybridge started taking sets of photos of objects in motion. Muybridge shot his first series of a horse just to settle a bet about whether all four of its hooves left the ground at the same time when it ran. But it was only a matter of time before the Zoetrope and the photograph wedded and gave birth to the motion picture.

In the 19th century some scientists thought the illusion was created by “persistence of vision,” the theory that images lingered in the eye for a brief period, sort of like the superstitious belief that by looking into a murder victim’s eyes you can see the last image he saw. Though we now know that isn’t how it works, scientists still aren’t completely sure why it happens. Current thinking is that we perceive motion based on differences between what we see from moment to moment, though even that doesn’t completely explain the phenomenon.

In the movie world, displaying 24 frames per second creates the illusion. Television’s 30 frames per second are a little more frequent.

Sound

The trick with getting movie sound to work is that it has to synchronize precisely with the picture. Even a delay of less than a second can produce a disturbing disconnect between audio and video, especially for shots of people talking.

Thus sound was a challenge that took decades to solve. During the silent era, cards edited into the action delivered dialogue. Though these made international distribution easy (just edit in new cards for each language), they interrupted the flow of the picture and forced people to read. The only sound was provided by musicians playing scores composed for the movies or improvising based on what was happening onscreen.

When “talkies” first hit theaters, sound was recorded on discs. Projectionists had to make sure to start the records at exactly the right moment so the audio and video would match. Even a show that started out on the right foot could go bad if the record skipped at all (which records tended to do). The movie Singin’ in the Rain has a hilarious sequence in which an early talkie’s sound gets out of sync and the characters look like they’re delivering each other’s lines.

The only way to make sound work reliably is to make it part of the film itself. This was done either optically (sound vibrations recorded as light fluctuations on the side of the film) or magnetically (a thin strip of recording tape built into the film). The picture and the sound were in slightly different spots in the projector, so editors had the tough task of getting everything to match up. But at least once they got it working it would work reliably.

Digital filmmaking stores sounds and images as data. The computers used to edit and play digital movies make everything match automatically, saving a ton of hassle in the editing stage.

Color

Years of teaching about movie history have taught me that some students tend to get confused about when Hollywood started making movies in color. So let’s start with the basics in simple terms: the studios started using color in the 1930s, not the 1950s. Thus color was not invented as part of the movie industry’s response to competition from television. Color became more common after television entered the media marketplace, but it was originally created a couple of decades earlier.

Actually, if you want to split hairs, many silent movies included color of one kind or another. Some were hand colored by artists who painted each individual frame, which of course was prohibitively expensive except for major releases in big cities. In the alternate, entire scenes were sometimes dyed a uniform color so at least they weren’t just plain black and white. Colors represented settings and moods, with blue for nighttime, green for outdoors, pink for romantic scenes, and so on.

In the early 1930s (not too long after movies started including sound), technicians figured out how to shoot in realistic-looking color. The process requires layered film. Rather than just recording a single black and white image, the new film recorded three overlapping images: one red, one blue and one green. These three colors could be combined to reproduce just about every visible color.

Technicolor, the first system to take advantage of this new innovation, was expensive. At first it cost so much that even the studios wouldn’t use it. Improvements brought the price down a bit, but color still tended to be the domain of big-budget studio productions. Further, the process produced extremely bright colors, making movies that looked a little too pretty to be real.

Thus many filmmakers continued to shoot in black and white well into the 1960s, either because they couldn’t afford color or because they wanted their movies to have a sense of gritty reality rather than ultra-colorful fantasy.

Widescreen

All pictures have an aspect ratio, the proportion of the image’s width to its height. Painters have a lot of leeway in this department, because they can stretch canvases to whatever proportion they like. Filmmakers, on the other hand, have to stick to aspect ratios that will work with cameras and projectors.

Edison’s studio established the movies’ ratio at 4:3 (or 1.33:1 if you prefer decimals), a proportion based on classical Greek art geometry. So if a movie screen was four feet wide, it would need to be three feet high. An eight foot wide screen would be six feet high, and so on. In 1931 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (the Oscars people) made a slight adjustment in the ratio (changing it to 1.37:1), but otherwise it remained the same for decades.

Then along came television. TV screens were absolutely locked into the 4:3 ratio, which gave movie folks an opportunity for a competitive edge. They began looking for ways to make images wider, creating a greater sense of largeness and importance.

Using anamorphic techniques, widescreen movies could be shown by making just a few adjustments in existing projectors. Other widescreen formats required larger film, which in turn required new projectors. VistaVision ran the film through the camera sideways in order to record a wider picture, and Cinerama actually split the picture up into three parts, requiring three perfectly synchronized projectors to show a movie.

The U.S. television industry didn’t enter the world of wider aspect ratios until HDTV came along in the 21st century. The new format uses a 16:9 ratio (or 1.85:1 for decimal fans), also commonly used in the movie business.

Digital Moviemaking

Making movies using film is a colossal pain in the butt. Film is expensive to buy, expensive to process, temperamental, non-reusable and – worst of all – you can’t tell what you got until after it’s been developed. On big budget Hollywood productions, that requires “rushes” (also known as “dailies”), rapidly-made prints of the day’s work used just to make sure that nothing got messed up.

Editing film is also a difficult process requiring expensive machinery and skilled professionals. If the edit isn’t done exactly right (or if the director sees the result and wants to make a change), a new copy of the film has to be made and the process starts over again.

Digital cinematography solves a lot of these problems. Whether moviemakers use tapes, discs or other ways to record the data, digital media are considerably cheaper than film. It requires no processing. It’s easy to edit. And best of all, you can instantly see exactly what you got by playing back what you just shot. Don’t like it? Erase the old version (or save it for the blooper reel) and shoot another one.

Of course cameras for shooting theatrical release movies are more complex, higher resolution and considerably more expensive than a consumer camcorder. But they’re still far cheaper than making movies the old fashioned way.

This should be a real blessing to the Hollywood studios, as digital production allows them to cut expenses and fire the people who used to do some of the now-unnecessary parts of the job. But the new technology has a downside as well. Because it makes production so much cheaper, digital cinematography opens the market up to competition from independent producers who would never have been able to afford to make movies on film.

Three-D

Any business that falls on hard financial times may resort to desperate measures such as gimmicks to draw customers. The movie business is no exception. In addition to tackling taboo topics and improving image quality, Hollywood tried to get a competitive edge on television by shooting some movies in 3D.

One of the ways our brains perceive depth is by comparing the differences between images from the right eye with images from the left. Movies recreate this effect by shooting two separate images and then combining them into a single picture. Viewers put on polarized glasses with lenses that block one of the two images for each eye, thus allowing them to “see in 3D.”

The technology used back in the 1950s wasn’t exactly the best, ensuring that 3D was a temporary ticket-selling novelty rather than a legitimate filmmaking technique. Likewise the version that emerged briefly in the 1980s failed to catch on.

The latest wave of 3D movies – which began in 2003 – appears to be a bit more successful. Changes in technology have improved image quality and reduced some of the eye-straining problems that plagued 3D in the past.

The big stumbling block at this point is creative rather than technical. Some directors under-use their equipment, shooting movies that look pretty much the same in 2D as they do in 3D. On the other hand, some over-use 3D, interrupting the flow of their storytelling to plug in long action sequences that don’t accomplish anything other than adding a gee-whiz for 3D audiences.

Production

The movie business is a three-step process. Most of what we think about when we use the term “moviemaking” is the first step: production.

Studio-made movies begin life in the development stage. Somebody comes up with an idea that seems like it would be a good movie, and she tries to convince the people who control the money that she’s right. If the movie will be based on a novel or other pre-existing work, the studio will have to buy the option to film it. Generally a screenwriter will prepare a first-draft script and a treatment in this stage. Many projects end up stuck in “development hell,” never moving beyond the planning stage.

If the studio “green lights” the idea, the movie enters pre-production. Based on the allotted budget, the producer hires everyone who will work on the picture. Often the script is storyboarded (illustrated with concept drawings so everyone can get an idea of what the final product should look like). Locations are scouted, sets are designed, deals are made with actors’ agents and so on.

Once everything’s ready to go, production starts. In movies about movies, this almost always seems to be the stage taking place. Lighting and sound are set, cameras roll, actors deliver their lines, the director yells “cut!” and the whole process starts over again.

When all the footage has been shot, the picture moves to post-production. Now editors labor to cut the shots together into the right sequence. Composers, sound effects technicians and visual effects technicians work their magic. Some movies are shown to test audiences, particularly if the filmmakers aren’t quite sure whether one ending will work better than another. And if mistakes are found, sometimes reshoots are necessary (going temporarily back to the production phase to make up for flawed footage).

With a little luck and a lot of hard work by a lot of people, at the end of the whole mess they’ve got a movie.

Distribution

Once the movie is “in the can” (completely done and ready to be shown to the public), it’s entrusted to distributors. On the surface this is a much simpler process than production, as the distributor’s two big jobs are to make copies of the movie and get them to theaters. And theaters with digital projectors can download movies from the distributor directly, eliminating the need for physical copies.

Reality is a bit more complicated. Distributors have to work with theaters’ schedules, making sure that their movies get shown in good theaters at popular times. Distributing movies to foreign markets adds more layers of complexity.

The distribution department at the studio is also responsible for promoting the movie. That includes previews to show during other movies, TV ads, newspaper ads, press junkets that allow reporters to interview the stars, and so on.

Distributors also handle movies’ release to disc, Red Box, Netflix, pay per view, premium TV networks, basic cable and broadcast. Some movies never see theaters, going straight from production to the home video market.

Exhibition

Because if you produce a movie and distribute a movie, people have to be able to watch it, right?

For the first 70-80 years of its existence, movie exhibition was a relatively simple business. Theaters had one screen each, so they booked movies one at a time (kiddie matinees and midnight shows notwithstanding).

Then in 1962 Kansas City theater owner Stanley Durwood had an idea. He realized that if he divided his one large, money-losing theater into two smaller theaters, he could draw in more customers without increasing the number of ticket takers and popcorn sellers he had to pay. His new scheme was such a big success that he founded a company, American Multi-Cinema, to open multi-screen theaters across the country.

By the 1990s the multiplex had almost completely replaced single-screen operations except for smaller theaters specializing in independent “art” movies. AMC and its competitors run many locations with dozens of screens. Thus audiences now have more movies to choose from.

The Studio System

Like just about every other industry, the movie business is dominated by a small group of large corporations. Currently most U.S. film production comes from the “big six”: Time Warner, Viacom (Paramount), NewsCorp (Fox), Disney, Sony (Columbia) and Comcast/GE (Universal).

In the Golden Age, studios (a slightly different set back then) held a solid lock on the industry. Stars were employees just like everyone else, and if a director wanted to use an actor under contract to another studio then he had to bargain for permission. They also used tactics such as block booking to force theaters to show whatever the studios produced.

Thanks to competition and legal action, the studios gradually lost their stranglehold on the movie world. Though they’re still exceptionally powerful players, they’re no longer the only ones in the game.

Coattails

Making a movie costs a ton of money, especially if you’re making a big Hollywood production. A successful picture can earn back many times the investment required to get it made and distributed. But even for a big corporation, hundreds of millions of dollars is a lot of money to gamble on a single product.

In order to reduce risk, Hollywood tends to churn out movies that are in some way related to previous successes. Some are sequels or follow-up installments in a series. Some are remakes of older American pictures or movies from other countries.

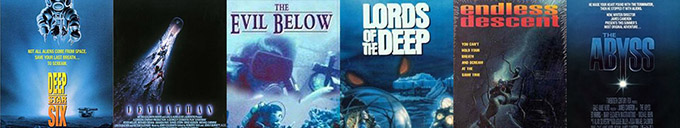

Sometimes studios even try to “scoop” each other. For example, when word leaked out that James Cameron (who had recently directed the hit sequel to Alien) was working about a movie set underwater, rival studios rushed sea monster movies into production and got them to theaters before The Abyss was done.

And if you find that a bit shady, consider the fine art of the “mockbuster.” Some smaller production companies with limited budgets have started making movies with titles and boxes that look a lot like popular, expensive studio productions. For example, Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds was beaten to the video rental shelves by at least two other versions of the same story. As all the different versions were based at least loosely on a novel that had been in the public domain for decades, there was little Paramount or Dreamworks could do about the knock-offs.

The Box Office

Success and failure of theatrically-released movies is measured by “box office,” which is simply the amount of money people pay to see them. It’s a much simpler measurement system than the more complicated audience measurements in other media such as magazines and television.

Though the numbers are straightforward enough, they can paint a complex picture of movie success. Take a look at Box Office Mojo, a web site that specializes in financial figures from the movie industry. Movie success – and its evil opposite – can be calculated in just about any conceivable way. Need to know which movie did the most business over Thanksgiving weekend? It’s there? How about the best among movies that opened the Wednesday before Thanksgiving rather than the Friday after? That’s there too. It also has the record-setter for drops in business after Thanksgiving.

And so on.

The Oscars

Once a year the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences hands out the Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars. In theory the awards recognize the best the film industry has to offer.

In practice, however, many critics charge that the Oscars have less to do with brilliant work and more to do with promoting movies. George C. Scott caused a stir in 1970 when he refused to accept the Best Actor Oscar for his work on Patton, describing the competition as a “meat parade.”

There’s a fair amount of support for this criticism. Of all the pre-Oscar prediction columns run in newspapers and magazines, one of the most consistently accurate is the Wall Street Journal’s list of who stands to get paid the most in bonus contract money if their movies win. Further, the awards tend to follow Hollywood trends. When the studios are trying to encourage audiences to go see less expensive, non-blockbuster productions, such movies tend to do better in the awards.

MSG CASE STUDY: GENDER

“Best Directress”

In 2010 The Onion (a humor site) joked that Kathryn Bigelow won the first ever Academy Award for Best Directress. In truth she won the Oscar for Best Director. But she was the first woman in the Academy’s history to ever win the award.

She was also only the fourth woman ever nominated. Greta Gerwig’s nomination in 2018 brings the total to five in the 90-year history of the Oscars.

This is of course much different from other Oscar categories. Half of all acting nominees have been women (because of course men and women have their own categories for acting). For decades women have been playing prominent roles in other realms, such as the crucial fields of screenwriting and film editing.

But the lack of female nominees for directing reflects the lack of women sitting in the “driver’s seat“ of big Hollywood productions. Of the five female nominees, Bigelow was the only one who was neither a foreign nor an independent director.

The Paramount Decision

Until the late 1940s, the studios held vertical integration control over the movie industry. This means that there were only a handful of studios in the business, and each studio controlled all three steps in its own production / distribution / exhibition process.

The Justice Department saw this level of control as a violation of antitrust laws, and eventually it got the Supreme Court to agree. The legendary “Paramount Decision” ordered the studios to give up control of at least one part of the business.

The choice wasn’t hard. By giving up the exhibition stage, the studios complied with the court’s order without really surrendering much of their power. After all, without the movies produced and distributed by the studios, what would the theaters show?

Though some studios have come and gone over the years, conditions haven’t changed much overall in the past decades.

Working for a Studio

Jobs on studio productions tend to be highly specialized. If a company is going to spend $100 million to produce and distribute a movie, it wants to make sure that everyone involved is good at their jobs. Of course that’s a spiral of expense. The more skilled professionals you hire to do something, the more that something is going to cost.

Movies begin in the development stage with a producer, someone who thinks this particular project is a good idea. Generally she’ll work with a screenwriter to come up with a script and a treatment (a brief summary) at this point.

If the project gets a green light, they’ll generally start by bringing a director on board. In the “auteur theory” of movie production, the director is in charge of the picture’s creative vision. He works closely with casting directors to make sure that the movie gets the actors he wants (and can afford). He also supervises the work of technical creative people such as cinematographers, composers and editors.

Each department in the production process employs many people. Just watch the end credits of any major Hollywood release to get an idea of how many folks it takes to make a movie.

Hollywood Shuffle

Producing a movie comes with your choice of price tags. On one extreme, you could make a video for YouTube. If that’s the limit of your ambition, you probably don’t need any more career advice from me. Go to it. And yes, believe it or not, some people do make money at the low end of the production value scale (though you probably shouldn’t quit your day job right away).

At the opposite end lies the studio production. These cost on average somewhere around $100 million to produce and distribute. If you make the average household income and save half of your money every year, it will take you a mere 4000 years to save up enough to pay for one of these.

In between are movies that don’t cost more than you could ever pay but at the same time have at least some mainstream marketability. Low prices for movies that have made more than a million dollars in the U.S. range from the cost of a good used car (El Mariachi) to the cost of a nice house in the Kansas City suburbs (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre).

One independent producer found a unique way to pay for his movie. Robert Townsend wanted to make a comedy criticizing racism in the movie industry. Guessing that he wouldn’t have much luck getting a studio to pay for it, he decided to get the financing together on his own. He managed to put together around $100,000 by applying for every credit card that sent him an application. He made Hollywood Shuffle using the cards to pay his actors in gas and groceries, and the movie was a hit with audiences and critics alike.

Getting Started

It used to be easy to give first piece of advice for getting started in the movie business: move to Los Angeles. The city is still the “movie capital of the world,” but many other places throughout the country also have active filmmaking community. And there are good film programs at universities other than UCLA and USC.

To be sure, most studio jobs will probably require relocation to California. One of the common entry-level positions – production assistant – will keep you in the studio offices most of the time. The same applies to readers, those hapless folks who go through the piles of scripts studios and producers receive from aspiring screenwriters.

On the other hand, work is where you find it. Outside Hollywood, many jobs in front of and behind the cameras are work on industrial films, movies that help viewers learn the benefits of joining the seafarers’ union or operate the new W6000 Open MRI Scanner. Still, a paycheck is a paycheck. The experience doesn’t exactly hurt, either. You never know where it might lead.

Noise in Theaters

It’s a tricky business, figuring out how much noise you’re allowed to make in a movie theater. Extreme cases are easy enough. If you’re at a midnight screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, you’ll stick out like a sore thumb if you aren’t yelling at the screen. On the other hand, if you go to an “art movie” then it’s best to watch quietly.

For most movies, however, proper etiquette varies from theater to theater. Back when the Indian Springs Mall in Kansas City Kansas still had theaters, it was common practice for audience members to freely express their opinions. Indeed, the comments were often more entertaining than the movies themselves. But if you’re in the Alamo Drafthouse theaters in Austin, Texas, don’t talk. Don’t even text. The theater staff aggressively ejects anyone who creates a disturbance of any kind.

The talk / don’t talk line has been further blurred as people grow used to watching movies at home. Psychologically, this tends to make movie theaters an extension of the living room rather than kin to live theater venues where talking would be intensely disrespectful to performers and audiences alike.

Colorization

In 1985, Ted Turner announced that he planned to colorize Citizen Kane. The colorization process used computers to add color to black and white movies, and Turner-owned MGM had already used the process on several classic movies.

Turner and others who owned the rights to lots of black and white movies saw colorization as a way to make new money from old pictures. Most folks didn’t seem to have much interest in older movies. But if the old movies were in color, the owners reasoned, they’d be more accessible to modern audiences. Or at least colorization was enough of a novelty to draw viewers curious about the “new look.”

Trouble was, the new look was awful. The process wasn’t sophisticated enough to produce truly realistic-looking color. Criticism was particularly harsh for the treatment of black actors, who often ended up the same color as wood tabletops.

And even if the process had been better than it was, the whole idea was still problematic. Some black and white movies from the 1930s and 40s would probably have been shot in color if the option had been available. Others, however, were deliberately shot in black and white to achieve the visual effect the director wanted.

Debate raged in classrooms and boardrooms. When Congress held hearings on the subject, the owners backed off and reduced or eliminated their colorization efforts.

And what happened to Citizen Kane? When the movie was originally made, director Orson Welles feared interference from the movie’s fictionalized target, William Randolph Hearst. So he made sure his contract with the studio specified that the movie couldn’t be altered in any way without his consent. Thus Turner never had the right to colorize it to begin with.

Shaky Cam

One of the great enigmas of filmmaking is that often making a movie look bad is the best way to make it look good. Shooting with substandard-quality film, cutting awkwardly and using other “amateur” techniques can help distance pictures from the well-crafted, slick and – some say – dishonest world of Hollywood blockbusters.

Directors going for such a rough look and feel frequently resort to a technique nicknamed “shaky cam.” Shooting using a hand-held camera without a tripod or a dolly makes the image bounce around, looking “shaky.” The idea is to give the picture a “documentary” appearance, as if the visuals were shot as a spur-of-the-moment reaction to a spontaneous event rather than carefully-planned footage of a scene arranged in advance.

The technique is particularly common in low budget horror movies such as The Blair Witch Project. On one hand, it’s an easy trick to pull off. And it usually achieves the result the director is after. On the other hand, some critics argue that the technique has become so over-used that now it’s a cliché.

Further, for better or worse, shaky cam can produce undesirable physical effects in some audience members. When our eyes tell us we’re moving but everything else in our bodies tells us we aren’t, the disconnect can cause nausea (sort of like seasickness only in reverse). Screenings of Cloverfield in AMC theaters were accompanied by warnings that the picture might make some viewers ill.

Movies and Truth

French new wave filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard once remarked that “the cinema is truth at 24 frames per second.” No other medium combines visual and audio reproduction of the “real world” in such a larger-than-life presentation. Epic space battles, elaborate musical numbers and other elements we know can’t be objectively “real” nonetheless impress us as somehow “true.”

Thus some critics argue that anytime filmmakers tackle an actual, historical subject that they need to be particularly careful about sticking to the facts. Amadeus, a movie about the rivalry between Wolfgang Mozart and fellow composer Antonio Salieri, drew critical fire for not sticking strictly to what historians know – or at least strongly suspect – about the two men. The movie’s creators replied that their work was intended to explore genius and envy as general human traits rather than to present the biographies of specific individuals.

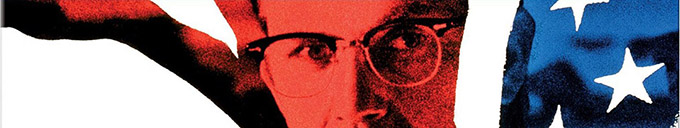

The issue is even more divisive when not everyone agrees about the truth. Oliver Stone’s JFK ignited a storm of criticism, some of it downright vicious, for questioning the government’s “official” version of the facts surrounding the assassination of John F. Kennedy. One of the “problems” was the director’s decision to blend actual, historical footage with dramatic re-creations.

The Hays Code

“Movies are immoral. They present scandalous material that tends to corrupt everyone who watches them.” The criticisms are as old as the movies themselves. Whether justified or not, the studios must deal with them nonetheless.

In the early 1930s, the anti-movie movement was particularly strong. Thanks to sound technology and the Great Depression, movies were an immensely popular entertainment medium. Risqué content onscreen and scandals behind the scenes gave moral crusaders all the ammunition they needed to attack the industry. Further, the Supreme Court had ruled that movies weren’t protected by the First Amendment (a decision that was later reversed).

In order to head off government regulation, the movie studios set up a system of self-censorship called the Hayes Code. The code was named after Will Hays, the head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (the studios’ industry association).

In 1934 the Production Code Administration began enforcing the rules. Studios weren’t allowed to make movies that violated any part of the code. As a result, several big Hollywood movies underwent significant change during the planning stages in order to prevent them from being blocked by the PCA prior to distribution.

Some of the rules were obvious stuff: strict limits on nudity and graphic violence. Drug and alcohol abuse were forbidden, and crime couldn’t be depicted unless the criminals were defeated by the forces of law and order. The code also prohibited even mild profanity.

A few of the rules caused problems, such as the requirement that “prominent people and citizenry of other nations shall be represented fairly.” When Warner Bros. started making anti-Nazi movies prior to World War Two, pro-German groups argued that they violated the Hays Code.

And some of the rules seem completely bizarre by modern standards, such as the rule against interracial relationships.

The MPAA Ratings

By the mid-1960s, the movie industry was forced to recognize that the old Hays Code wasn’t working anymore. Hollywood faced ever-increasing competition from independent producers and foreign filmmakers who weren’t bound by the code. Society’s morals had changed a bit over the past three decades, rendering some of the rules counterproductive if not completely obsolete. And worst of all, many Hollywood producers were making movies that openly violated the code without suffering repercussions from the enforcement office.

Recognizing the need to make a change, in 1968 the Motion Picture Association of America (the new name of the MPPDA) replaced the Hays Code with the rating system in place today. Or at least more or less the same system; the ratings have been “tweaked” a little over the years.

Unlike the Hays Code, the new system didn’t ban movies for rules violations. Instead, it was designed to stick a label on each new release that parents could use to determine whether or not it was appropriate to let their kids go see it (or in the case of an R or NC-17 movie, to keep some or all kids out of the theater).

Though not imposing outright bans, the Classification and Rating Administration nonetheless wields a lot of power in the movie industry. If a movie gets an R rather than a PG-13, it automatically loses a good-sized chunk of the 16-and-under audience (though it may pick up other viewers who regard PG-13 movies as “too tame”). An NC-17, on the other hand, can be a kiss of death. Many movie theater chains won’t screen pictures with the “adults only” rating, and some video retailers won’t stock them, either.

MSG CASE STUDY: SEX AND VIOLENCE

The Look

Famous film critic Robin Wood once made an interesting observation about horror movies in general and slasher movies in particular: they tended to feature what he called “the look.”

What he noticed in movies such as Halloween and Friday the 13th was that often right before the killer claims another victim, directors were using POV – point of view – shots from the slasher’s perspective. In effect the audience was experiencing the build-up to the crime through the murderer’s eyes.

Wood’s method of studying film led him to focus on what filmmakers did and why they did it. Thus he noted that “the look” encouraged slasher movie audience members to see things from the killer’s perspective. As the victims were often scantily-clad or naked women, Wood was concerned that men were being encouraged to get their sexual desires mixed up with voyeurism and psychotic murder.

A POV shot doesn’t automatically signal viewers that they’re expected to sympathize with the character whose view they’re experiencing. But Wood made some good points about the relationship between “the look” and themes of misogyny and sexual exploitation.

The Hollywood Ten

During the Red Scare in the 1950s, anti-Communist forces in the government singled out the media as major targets for blacklisting. Anyone with Communist ties or even leftist leanings could find themselves fired from their jobs and unable to find new work.

In Washington, the House Un-American Activities Committee began a “witch hunt.” It issued subpoenas to many people in Hollywood ordering them to appear before the committee and testify. The committee expected them not only to admit their own Communist ties but also to identify other people who might also be Communists.

The HUAC was inconsistent in its handling of its victims. Some testified honestly that they weren’t Communists and didn’t know of anyone who was. In some cases that was enough, but in others the person ended up on the blacklist anyway.

Ten screenwriters and directors who appeared before the committee refused to testify, citing their Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate themselves. Unimpressed, the HUAC had the “Hollywood Ten” thrown in jail for contempt of Congress. Even after they were released, for some time they had trouble finding work. Like other people on the blacklist, the only way they could make a living at their craft was to hire “fronts,” non-blacklisted people who pretended to be the authors of scripts actually written by people on the list.

Coming to America

In 1988 Paramount Studio released Coming to America. Starring Eddie Murphy and directed by John Landis, the movie told the story of an African prince who traveled to the United States in search of freedom from his family and an arranged marriage. Though the picture wasn’t a creative or financial high point for anyone involved, it was a moderately successful comedy.

Then it became the subject of a lawsuit.

Washington Post columnist Art Buchwald originally sold the idea for the movie to Paramount six years earlier. The studio later decided to abandon the project but then went ahead and shot the movie anyway. Murphy was given sole screen credit for the story, and the studio didn’t pay Buchwald a dime. So he sued for breach of contract.

Here’s where it really gets fun. The studio claimed that even if Buchwald was the story’s original author, he still wasn’t entitled to any money. The contract between the studio and the writer entitled him to payment based only on “net profit.” And the movie hadn’t turned a “net profit” based on the contract’s definition, even though it earned nearly $300 million at the box office.

Buchwald’s lawsuit exposed the movie industry’s bizarre accounting practices, which the court called “unconscionable” when it found in favor of Buchwald.

Though he sought nearly $6.2 million in damages, the court awarded him only $150,000 (small compensation given that he’d already spent more than $200,000 on legal fees). For its part, Paramount dropped nearly $3 million on attorneys’ fees. So other than the lawyers, nobody really won.

The Kansas Film Board

Once upon a time, many states had their own movie censorship boards. When movies first started gaining widespread appeal in the 1910s, state governments reacted by setting up boards to regulate movies in the name of public morals.

Though some states had lenient boards (or no boards at all), Kansas was notorious for having one of the strictest boards in the nation. Even something as simple as a scene in which characters danced could end up with thick black bars placed across the picture. And of course anything more risqué than that was cut out altogether.

This created problems for distributors. Coming up with different versions of their products for different states was a pain. And once “talkies” hit the market, cutting a scene from a movie meant that the visuals wouldn’t be in sync with the audio on the accompanying disc.

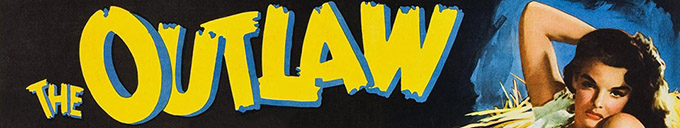

Though some distributors went along with the rules, others resisted. After the board banned The Outlaw from Warner Bros., the studio refused to let any of its other movies be shown in Kansas. And some smaller distributors sidestepped the law by cutting their movies down in order to earn the card required before movies could be shown in the state and then shipping the original, uncut version to theaters.

Then in 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court dealt a blow to state film boards throughout the country when it ruled that movies were protected by the First Amendment and could only be banned if they were legally obscene. Though the Kansas board continued operating for another dozen years, it no longer had the power to censor movies for the long list of reasons it used to use.