I apologize in part for the name of this chapter. Normally calling a section “Newspapers: Dawn of an Age” would be as informative as “Shoelaces: They’re a Thing” or “Pepsi: Drink It With Your Mouth.” But rather than having no meaning at all, this chapter title actually has two meanings.

First, newspapers gave birth to the Information Age. In the late 19th century, the newspaper industry was the first to begin catering to the information needs of common folk. By making their products affordable and providing content that appealed to the average reader, publishers helped promote literacy and democracy.

Now a new age is upon us. The thirst for information – first stirred by newspapers – has overtaken its “parent.” Fewer and fewer readers have the patience for “dead tree” newspapers, turning instead to faster, more accessible info sources such as the Web. Some say newspapers are dying. Others believe they’re transforming, converging with other media in ways that aren’t always a comfortable fit.

In this chapter – and again in Chapter 13 – we’ll take a look at where the current crossroads may lead.

The Press Barons

The Industrial Age was the domain of barons. Whole industries were controlled by single companies – called “trusts” – and at their heads stood individual men. John D. Rockefeller was the Oil Baron. Andrew Carnegie was the Steel Baron. Just about everything from railroads to bananas were controlled by trusts with barons at the helm.

Although the newspaper industry tended in the 19th century (as it does today) to be local rather than national or global, in big cities (or even medium-sized ones) newspapers turned out to be profitable enough to create “press barons.” The first of these captains of media industry was James Gordon Bennett.

He founded his newspaper – the New York Herald – in 1835, and a mere ten years later it was the most popular daily in the nation. Indeed, he called his creation “the most largely circulated journal in the world,” and not without justification. Bennett’s philosophy was that the newspaper’s purpose was “not to instruct but to startle.” Apparently he knew what his readers wanted.

After the Civil War, he handed the reins over to his son, James Gordon Jr. Gordon followed in his father’s footsteps, thrilling readers by sponsoring Henry Morton Stanley’s expedition to Africa to search for the missing David Livingstone. He also led a turbulent private life, on one occasion ruining an engagement by showing up at his fiancée’s family’s house dead drunk and urinating into the fireplace (some accounts say his target was a grand piano).

But of course the Herald was printed in New York City, which even in the 19th century had a population big enough to make just about any product profitable. What about smaller towns farther west?

Even a “cow town” the size of Kansas City still managed to produce a press baron: William Rockhill Nelson. His newspaper – The Kansas City Star – made him wealthy enough to co-found the city’s world-class art museum: The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art.

Poor Richard

You’ve heard these famous quotes:

“Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead.

“He that lieth down with Dogs, shall rise up with Fleas.

“Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.

“A penny saved is a penny earned.”

You probably already knew those were all from famous American statesman Benjamin Franklin. You may even have known that they were from Poor Richard’s Almanack, which Franklin published under the pseudonym Richard Saunders.

Less well-known, however, is Franklin’s work on the Pennsylvania Gazette, a small “news sheet” he purchased in 1729. He swiftly turned the publication into a vehicle for his personal style of satire, using its pages to poke fun at contemporary society. In the newspaper’s pages he sharpened the wit he would later employ in his famous Almanack and of course in the Continental Congress.

Sadly, the brilliant mind that invented bifocals and the Franklin stove was too busy to add much to printing technology. But his work as a news reporter as well as an essayist set the standard for American journalism for years to come.

The Anti-Lynching Crusader

The journalism career of Ida B. Wells began on May 4, 1884, when a conductor ordered her to give up her seat in a train car reserved for white people. When she refused, the conductor and two other men physically dragged her out of the car. The experience inspired her to write an article for The Living Way, a church weekly in Memphis.

She continued to write for newspapers while working a day job as an elementary school teacher. Then in 1889 she became editor and co-owner of Free Speech and Headlight, a newspaper devoted to covering civil rights issues.

The anti-lynching campaign became Wells’ particular passion. After three of her friends were murdered for defending their store against a mob, Wells wrote an article urging black people to leave Memphis, “a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.” More than 6,000 people left town, and others organized boycotts.

In response to threats against her life, she moved from Memphis to Chicago, writing for the Chicago Conservator and The New York Age. In 1895 she married newspaper editor Ferdinand L. Barnett, becoming one of the first American women to break with tradition by keeping her own last name.

Wells was particularly concerned about the economic aspects of lynching. In her writing – particularly Southern Horrors, a famous anti-lynching pamphlet – she exposed the real motives behind racist violence. Though excuses ranged from alleged rape to public drunkenness, she argued, white mobs lynched black men because they were afraid of competition from black-owned businesses.

During a trip to Europe, she became the first black woman to write for a mainstream, white-owned newspaper, The Daily Inter-Ocean. She also bucked the trend among female authors to write in a “womanly” manner, instead adopting the same tone and style as her male colleagues.

The Wizard of Ooze

William Randolph Hearst. Even more than half a century after his death, this media giant’s influence can still be felt. If you’re in doubt, check the ownership info for your local TV stations and see if perhaps one or more of them belongs to the Hearst Corporation. Or check the indicia of your favorite magazine. It too might be a Hearst publication.

Hearst started life as a rich kid, the son of Comstock-gold-mine-wealthy George Hearst. But the part of daddy’s empire that attracted him most was the newspaper end, particularly The San Francisco Examiner. He aggressively hired the best writers – including Mark Twain – away from other newspapers and bought the Examiner the latest in printing technology.

His success in San Francisco led him – with some help from his mother – to buy into the New York market. He purchased The New York Morning Journal, a small, failing newspaper, and soon had it competing head-to-head with publishing giant Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. Later he expanded his empire to include newspapers in cities across the country.

Hearst and Pulitzer both sold newspapers using what came to be known as “yellow journalism.” Even in an age not exactly known for sober news coverage, the Journal and World were famous for sensationalizing even the simplest news story. Crime stories in particular were recounted in lurid detail and structured as morality tales, warnings that “crime doesn’t pay.”

Of course the man himself was no stranger to scandal. He had a long-standing adulterous relationship with movie star Marion Davies, and movie producer Thomas Ince died on Hearst’s yacht under mysterious circumstances.

In addition to his publishing empire, Hearst’s legacy includes a huge, art-filled mansion at San Simeon, California, which the company donated to the state after his death.

Protecting the Tablecloth

In the 1890s, The New York Times was a small newspaper just barely getting by in a crowded market dominated by the “yellow journalism” of Hearst’s New York Journal and Pulitzer’s New York World. So when a new publisher, Adolph Ochs, took over in 1896, there was nowhere to go but up.

Ochs decided to compete with the big boys by not competing with them. Rather than offer sensationalized scandal-mongering, he hired Carr Van Anda to help the Times pursue a path of objective journalism, reporting facts rather than biased opinion and focusing on socially-relevant stories about politics and science rather than lurid crime and celebrity gossip.

To be sure, the move was a gamble. Ochs dropped the price, increasing its appeal to the lower classes (not historically known for their love of sober news coverage). But with slogans such as “It will not soil the breakfast linen” (implying that the yellow press “bled” all over the morning tablecloth) and the legendary “All the news that’s fit to print,” Ochs and Van Anda made a success of their new venture.

And what a success it was. This new style of journalism swiftly caught on with both readers and reporters. As the fortunes of the yellow press waned, “objective” reporting became the industry standard for news coverage in the 20th century.

McPaper

Newspapers are supposed to be boring, or at least look boring. Nobody in the industry would have come out and said it, but for most of the 20th century the standard prevailed nonetheless.

Thus the Gannett newspaper chain caused quite a stir in 1982 when it launched USA Today. The new newspaper was designed for national rather than metropolitan distribution. But more than that, it was flashy. It was colorful. Infographics decorated its pages. Stories were short and simple.

At the time critics called it “McPaper,” implying that USA Today was more about marketing than about “nutritious” content. But in less than a year the new publication already had more than a million daily readers.

Success is hard to argue with. In the following decades, many struggling newspapers began to imitate the Gannett publication’s visual and editorial style. Successful competitors were slower to jump on the bandwagon. The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal both made it almost all the way to the 21st century without using anything but black ink for their front pages.

Now, however, the visual style that once drew insults is now the standard for the industry. To be sure, not everything pioneered by Gannett caught on. For example, few newspapers followed USA Today’s practice of printing ads on the front page. But for better or worse, the “McPaper” style is now in place just about everywhere.

Confederates and Copperheads

Everyone knows the Civil War divided the nation into North and South. What many history books don’t make clear is that even within the Union and the Confederacy opinion about slavery and secession wasn’t exactly uniform.

Divisions were particularly deep in the North, where some newspaper publishers supported Abraham Lincoln’s efforts to reunite the country and others favored allowing the Confederate states to leave the union. The latter group became known as “copperheads,” an insult implying that they gave no warning before they struck.

Many newspapers sought ways to avoid coming down strongly on one side or the other. For example, James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald supported candidates who ran against Lincoln in 1860 and 1864, but it also backed the Union’s cause.

In the South publishers were more uniformly behind the Confederacy, though some anti-slavery newspapers continued to publish even after the war started. However, as the tide of the conflict began to turn against the South and public opinion began to turn against the war, newspapers followed suit.

On both sides, the media brought the war back home in new ways. Though the work of photographers such as Matthew Brady couldn’t be printed directly in the newspapers (print technology wasn’t sophisticated enough at the time), photos of battlefield casualties did serve as the basis for drawings on front pages. Artists also observed battles directly, recording what they saw and passing it on to readers of illustrated publications such as Harper’s Weekly.

Mr. Hearst’s War

“You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.”

So the story goes: artist Frederick Remington sent a telegram to newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst saying that all seemed quiet in Cuba (a Spanish territory at the time) and that war was unlikely to erupt between the United States and Spain. Hearst allegedly cabled back that Remington should stay put because, well, you’ve already read the rest.

Historians generally agree that the publisher never sent such a cable. But they also agree that Hearst and his newspapers strongly supported the war against Spain and that their support and sensationalized coverage of the conflict helped sell a lot of newspapers.

Revolt had been brewing in Cuba for some time, with the United States waiting on the sidelines. When riots erupted between Cubans and Spanish soldiers – spurred in part by newspaper criticism of government policy – the battleship USS Maine steamed into Havana harbor, supposedly to provide protection for U.S. citizens in Cuba.

On February 15, 1898, a tremendous explosion destroyed the Maine, sinking the ship and killing most of the crew. The Navy’s investigation concluded that an explosion outside the hull set off explosives in the ship’s powder magazine, but Spanish authorities claimed that the explosion started inside the Maine. The issue remains unresolved to this day.

Hearst and other “war hawks” seized on the incident as justification for a full-scale war against the Spanish Empire. With a battle cry of “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” U.S. forces fought the Spanish not only in the Caribbean but also in the Pacific. The long-term fates of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines were strongly influenced by this largely one-sided war, which lasted a mere ten weeks.

With yellow journalism’s traditional lack of respect for accuracy, newspapers owned by Hearst and his biggest competitor, Joseph Pulitzer, presented readers with awful (in every sense of the word) stories about Spanish atrocities committed against helpless victims. U.S. tourists in Cuba were a particular target, where Hearst (with the help of drawings from Remington) claimed that officials were strip-searching American women. Even though many of the articles strained the limits of credulity, they nonetheless fanned the flames of public support for the war and left readers anxiously awaiting the next set of tales from abroad.

A President’s Downfall

On June 17, 1972, five men broke into the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. Caught in the act, their arrests led to an FBI investigation that uncovered links to members of the administration of President Richard Nixon.

Such incidents aren’t entirely uncommon in the world of politics, and the affair might have gone largely unnoticed if not for two things: Nixon and his aides tried to cover up the whole mess (often you’ll find that lying about being a crook is far worse than being a crook) and the media got ahold of the story.

An anonymous source who went by the name “Deep Throat” (which was also the name of a popular porn movie) contacted Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, meeting them in a parking garage in the middle of the night and feeding them tips to help them trace the cover-up conspiracy to the highest levels of the Executive Branch.

Though at first the administration accused the media of “scandal-mongering,” the evidence against the President swiftly began to mount. In particular, Nixon had recorded several Oval Office conversations in which he discussed cover-up efforts with subordinates. After he lost a court battle to keep the tapes from becoming public and being used as evidence against him, Nixon resigned from office to avoid impeachment.

A popular President might well have weathered the scandal with relatively minor damage to his reputation (as several other Presidents have proven before and since). But Nixon wasn’t popular. Division over the Vietnam War in particular had damaged his presidency, leaving him vulnerable to criticism, especially when he deserved it.

To be sure, many Americans were angrier at the news media for failing to support Nixon than they were at the President himself. On the other hand, journalism school enrollment hit an all-time high in 1974 as college students recognized the potential good reporting had to help change the world.

The Inverted Pyramid

Different kinds of writing are, well, different. Poets take a different approach to their writing than the work styles generally used by novelists. Screenwriters use different writing conventions from playwrights. And of course news reporting has its own terms and techniques as well.

Unlike many other kinds of writing, reporting is an actual job with a paycheck rather than something you do on your own time hoping that someday it’ll pay off. Because it’s work as well as fun, it comes with an obligation to serve the readers’ needs. And deadlines. Lots and lots of deadlines.

In order to write quickly and communicate effectively, reporters have developed a writing style called the inverted pyramid. An inverted pyramid story starts with the biggest, broadest, most important information first. Then as the story progresses the writer fills in the smaller, less important details until finally at the end she puts in anything that’s “nice to know” but doesn’t really need to be included.

Back in the print days, this was a function of the workflow. A reporter might finish a story in the afternoon and go through it with her editor before leaving work. But then it might not go to layout for some time, so the reporter might be at home asleep before the editor and the layout people determine that there isn’t quite enough room on the page for the entire piece. The inverted pyramid assures that the editor can cut the last paragraph or two without ruining the whole thing, which of course made it easier to edit at the last minute.

Of course in the Web world stories have as much space as they need. However, the inverted pyramid is more important now than ever. In the information-rich 21st century, few people have the time or energy to read page after page of a news story trying to figure out if it has anything relevant, useful or interesting to communicate. In the inverted pyramid, the writer tells the reader the important facts immediately. If that hooks him and gets him to read the rest of the piece, great. Even if he decides to skip the rest, at least he got the big stuff from the beginning.

The News Hole

Audiences read the newspaper for news, not for ads (with the possible exception of the classifieds). Traditionally, then, newspapers have considered themselves in the news business and plan their content accordingly.

However, in the layout department the exact opposite is the case. Ads go on pages first, and the news gets poured into whatever “news hole” remains. As a matter of timing, ads usually have to be submitted well in advance, so they’re available to the layout artists well before last-minute news stories are submitted. Further, advertising pays most of the newspaper’s bills, so cutting an ad for extra news will cost the publication money (and probably upset the advertiser as well).

In the online world, the news hole isn’t a great concern. Indeed, the more news the publication can generate, the more banners and skyscrapers the ad people can drop in next to it. Other media – particularly television – still face a news hole dilemma. As news production becomes more and more expensive and ads provide less and less money, the news hole and the amount of news to “plug” it continue to shrink.

Newspaper Types

The newspaper industry differentiates its product based on newspaper types. Here are some of the most common:

National dailies – Though most newspapers are local, a few have achieved success on the nationwide stage. The two American newspapers with the largest circulations – USA Today and The Wall Street Journal – are both national publications. USA Today is designed to appeal to a general audience, and the Journal is aimed more specifically at people in the business world.

Major metropolitan dailies – Every large city – and most medium-sized towns – in the United States has at least one daily newspaper. The New York Times straddles the fence between national and metropolitan; technically it’s a metro for New York City, but it’s also marketed across the country (especially the Sunday edition). Many of the key players in the newspaper business got their starts with metro dailies in smaller cities before moving into the big markets. William Randolph Hearst started in San Francisco, Joseph Pulitzer found his first big success in St. Louis, and Rupert Murdoch’s first newspaper was in Adelaide, Australia.

Small-town weeklies – In today’s media marketplace, small-town newspapers tend to come out once a week. Their stories tend to focus on human interest (bake sales, flower shows and the like) rather than “hard news.”

Alternative weeklies – Big cities often also have weekly newspapers, but these tend to be examples of the “alternative” press. They’re generally aimed at younger audiences, featuring stories about pop culture, the local club scene and the like. They’re also one of the last remaining bastions of serious investigative journalism.

Student newspapers – Because everybody has to learn somewhere. Many high schools and colleges support some kind of student-run publication, where aspiring journalists can begin learning the tricks of the trade.

Counting Readers

No matter what the medium, advertisers pay for ads based on how many audience members they reach. In the newspaper business, audience size is based on circulation. At its simplest, circulation is the number of copies printed and distributed. However, calculating exactly what advertisers want to know can be a tricky business.

For example, paid circulation is the number of copies a newspaper sells directly or distributes to subscribers. But this number doesn’t include copies given away for free. Some newspapers don’t dish out that many freebies, but others are more generous. USA Today is particularly well known for distributing free copies to colleges in order to get students into the habit of reading the newspaper.

Total readership includes not only circulation but also pass-along, the average number of readers per copy. For example, back when we still subscribed to The Kansas City Star my wife and I just got one copy of the newspaper, but two of us read it.

Newspaper readership is monitored by the Audit Bureau of Circulations, which keeps track of circulation and pass-along and generates reports that newspapers and advertisers can use to determine how much ads should cost.

Dealing with Declining Circulation

As everyone in the newspaper industry knows, readership has been slowly declining for some time now. Even as early as three or four decades ago, newspapers began noticing circulation difficulties.

The problem first cropped up in medium-sized towns such as Kansas City that had more than one metro-wide daily newspaper. In order to keep competition between two publications from killing them both, competitors entered into joint operating agreements. JOAs allowed both newspapers to come up with separate content, but their business and printing operations merged in order to save money. For awhile The Kansas City Times published in the morning, and then The Kansas City Star used the same presses to print an afternoon edition. Eventually, however, the Times folded altogether, leaving the Star as the city’s only daily newspaper.

Many newspapers have gone partially or even entirely online, though as mentioned above this isn’t a perfect solution to every circulation problem.

The industry has also tried increasing circulation by making content changes. Newspapers today tend to feature shorter stories and more colorful graphics than their relatives from the 19th and 20th centuries.

As a cost-cutting measure, many newspapers have gone from a full-sized broadsheet page to smaller, tabloid page measurements. And of course they’ve also closed “suburban” news offices, laid off staff and instituted other money-saving strategies.

Newspapers Unchained?

Back in the day, newspaper chains – sets of publications all owned by a single parent company – were the lords of all media. Newspapers tended to be “cash cows” that supplied healthy profits that chains could use to invest in other, riskier opportunities.

Now, of course, the tables have turned. Corporations previously known for their flagship newspapers have either moved on to other businesses or fallen on hard times.

However, not everything is gloom and doom in the newspaper industry. Chains of small-town newspapers are thriving where their bigger competitors have struggled. Rather than provide expensive national and international coverage (which is easily available via the Internet), the publications in these chains emphasize lean news operations specializing in local coverage that readers can’t get anywhere else.

Of course the owners of most major metropolitan dailies tend to be big corporations either in the newspaper business or as part of a diversified media empire. But even at the local level, the chain model is helping small newspapers cooperate with one another to help stay alive.

Getting a job

At a major metropolitan daily newspaper, most entry-level jobs are in reporting. Like any other business, newspapers tend to assign less desirable jobs (such as writing obituaries) to new employees, and once you’ve “paid your dues” you move on to more interesting work.

Non-writers also have career opportunities at newspapers working as photojournalists, graphic designers, layout artists and the like. Printing each issue requires press operators, and getting it out to readers is the job of circulation people. And of course advertising pays the bills, so someone has to go out and drum up ad sales.

The next step up in the promotion system is to an editing job. Larger newspapers employ several kinds of editors. Page editors are in charge of specific sections of the publication, such as local news, national news, sports, business, lifestyle, religion and the like. Copy editors are responsible for helping writers eliminate mistakes in their work. And above everyone else is an Editor-in-Chief and/or Managing Editor, making sure the whole operation runs as smoothly as possible.

Ultimately the publisher is answerable for the newspaper. In general he stays out of the day-to-day operations, intervening only in extreme cases. When President John F. Kennedy wanted The New York Times to hold back a story about the Cuban Missile Crisis, he called the newspaper’s publisher rather than the editors.

The Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer (pronounced “Pull-itzer,” not “Pyew-litzer”) Prizes are the most prestigious awards in newspaper journalism. Odd, then, that the man they’re named after wasn’t exactly a good journalist, at least by modern standards.

Like William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer made a fortune from “yellow journalism,” drawing readers with biased, sensationalized coverage of the news. Though his newspapers wouldn’t win many of the prizes that bear his name, they did work to expose corruption in government and big business.

More than that, however, they made Pulitzer wealthy enough to fund a series of prizes for outstanding newspaper work. Once a year the prizes are awarded by the Columbia University School of Journalism, which typically receives thousands of entries. Prizes are awarded in 14 categories, including “national affairs coverage,” “commentary” and so on. Printed and online newspapers are eligible, though magazines, radio and television news operations are not.

The Pulitzer Prize web site features copies of award-winning stories (as well as the work of the runners up), making it an excellent learning-by-example resource for aspiring journalists.

Professional Organizations

The newspaper industry has a strong history of independence from central control, leery not only of government authority but also of industry self-regulation. However, many journalists voluntarily join professional organizations. And such groups often have ethics codes.

The Society of Professional Journalists is the most prominent professional organization for reporters. The SPJ’s Code of Ethics begins with four basic principles:

- Seek Truth and Report It

- Minimize Harm

- Act Independently

- Be Accountable

Each of these principles imposes duties on good journalists. For example, in order to “act independently,” professionals must avoid conflicts of interest, refuse gifts, avoid bidding for news and so on.

Specialized professionals – such as photojournalists – also have organizations devoted specifically to their interests, such as the National Press Photographers Association. And these groups too have their own codes of ethics.

Unlike doctors and lawyers, however, professional journalists cannot be “disbarred” for breaking the rules. Though the SPJ can kick you out for ethics violations, you don’t have to be an SPJ member to hold a job in the newspaper business.

Codes of Conduct

Most newspapers have their own “in house” codes of conduct. These codes are usually based on the same professional principles as the SPJ Code. However, they’re likely to deal not only with the big concepts but also with the small details.

Imagine yourself as a reporter sitting down for an interview with a political candidate. The politician offers you a cup of coffee before you get started. Can you accept it? On the one hand, in American society “would you like a cup of coffee?” is a simple courtesy we routinely offer to one another whether or not we’re trying to win someone over. On the other hand, as a working reporter you’re not supposed to accept gifts from the people you interview.

The SPJ Code isn’t much help. It just says “refuse gifts,” which doesn’t help you determine whether or not a cup of coffee is a gift. But if you worked for the Kansas City Star, the newspaper’s code of conduct pins things down a little more: “For a soft drink, coffee, etc., of nominal value, staffers should use their best judgment.” So now you know that it’s officially your call. If the interviewee is just being polite, help yourself. But if you think she’s trying to buy your favor, you should probably pass.

And unlike organization codes, breaking your employer’s code of conduct will most certainly have consequences. Newspapers can and do fire journalists for breaking their rules.

Zenger Zings the Governor

In September 1734 The New York Weekly Journal printed articles about William Cosby, the governor of the colony of New York, accusing him of violating the rules of his office. Enraged, Cosby had copies of the newspaper gathered up and burned. He also had its publisher, John Peter Zenger, arrested for “seditious libel.”

In the days before the American Revolution (and Constitutional protection for free speech), truth was not a defense against a charge of libel. All the prosecutor had to prove was that Zenger printed something that damaged Cosby’s reputation. Indeed, the truth of the accusation just made the damage worse. So at trial the judge told the jurors that the only thing they had to decide was whether or not Zenger was responsible for printing the Journal’s articles, which of course he was.

However, Zenger’s attorney was Andrew Hamilton, one of the colonies’ best trial lawyers. Not about to lose an important case, he tried an extreme tactic: jury nullification. In his closing argument, he told the jury that they were free to decide Zenger was not guilty based on the truth of the stories, no matter what the judge said to the contrary.

After a short deliberation, the jury found in Zenger’s favor. In the resulting celebration, nobody remembered to let Zenger out of his cell until the next day.

Gouverneur Morris, one of the framers of the Constitution, later described Zenger’s acquittal as “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.”

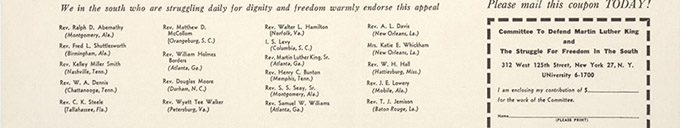

“Heed Their Rising Voices”

To help raise support for Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement, a group of activists and celebrities signed an appeal for help. Under the headline “Heed Their Rising Voices,” the appeal described some of the abuse Southern authorities had inflicted on people protesting for their rights.

On March 29, 1960, The New York Times printed the appeal as an ad. Though the text overall was an accurate description of the problem, it contained a few errors. For example, it said students were expelled from school in Montgomery, Alabama, for singing “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” on the state capitol steps. The song they actually sang was the National Anthem.

L.B. Sullivan, one of Montgomery’s three city commissioners, sued the Times for libel, claiming the ad damaged his reputation and the errors made the accusations false. In the segregationist South he had little trouble getting a court to award him $500,000.

The United States Supreme Court was another matter. Unanimously finding in favor of the Times, the justices declared Alabama’s libel law unconstitutional because it didn’t require public officials like Sullivan to prove “actual malice” – that the newspaper deliberately printed something false or showed reckless disregard for the truth.

This new standard made it much harder for elected officials (and later other public figures) to win libel suits, making it easier for journalists to cover politics without fear that innocent mistakes would cost them thousands of dollars.

The Pentagon Papers

The document’s title wasn’t breathtaking stuff: “United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense.” It was classified “Top Secret – Sensitive,” the last word indicating that it contained material that might embarrass the government if it ever became public. And so it did. The report concluded that four Presidential administrations – Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson – had been less than honest with the American people about the nature and extent of U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia.

Daniel Ellsberg, who had helped put the report together, felt the public had the right to know what was going on. So he “leaked” it to the press, supplying copies of the document to reporter Neil Sheehan at The New York Times and editor Ben Bradlee at The Washington Post. Both newspapers began to print stories about the report. And the government went to court asking judges to order the newspapers to stop.

The judge in New York agreed based on the classification of the document, which had become known as “The Pentagon Papers.” The judge in Washington, on the other hand, found that such a prior restraint – an order from the government stopping publication before it occurs – was prohibited by the First Amendment except under extreme circumstances that weren’t present in the Pentagon Papers.

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case directly and immediately rather than allowing it to take the usual months or even years to make it up the legal ladder. And in just a couple of days the justices reached their decision: the government hadn’t met the high burden required to impose a prior restraint, and the newspapers could print their stories.

In his opinion, Justice Hugo Black wrote “Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.”

Involuntarily “Out”

Billy Sipple was a national hero. He served in the Marine Corps in Vietnam until a shrapnel wound took him out of action. But better yet, he foiled an assassination attempt on the President. On September 22, 1975, Sipple was in a crowd of people watching as President Gerald Ford left a building in San Francisco. Suddenly he noticed that a woman standing nearby had drawn a gun. He lunged at Sara Jane Moore just as she pulled the trigger, knocking her aim off and preventing her from getting a clear shot at Ford.

The Secret Service praised him. The media praised him. And in his praise, San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen mentioned that Sipple was gay.

Though Sipple was active in the city’s gay community, neither his employer nor his family back home in Detroit knew about his orientation. And being “outed” was a big deal in 1975, when anti-homosexual prejudice was stronger than it is now (not that there isn’t plenty left even today).

So Sipple sued the Chronicle and several other newspapers that picked up the story. He asked the court to award him $15 million, alleging that the newspapers invaded his privacy by publicly disclosing a private fact. The legal battles continued for nearly a decade before a California appeals court finally held that Sipple had become news whether he wanted to or not and that his orientation was a legitimate part of the story.

Reporters Are the Same as Everyone Else

Thanks to the First Amendment, newspapers tend not to be the direct targets of a lot of government regulation. However, that still leaves shelves full of laws that apply to journalists the same as they apply to everyone else. NPR reporter Larry Matthews found out the 18-months-in-prison hard way that when you get busted trading kiddie porn on the Internet, the court doesn’t care if you were doing it in the course of working on a story or if that’s just how you get your jollies.

On the other hand, Constitutional problems arise when a law that seems like it would apply to everyone equally ends up hitting journalists disproportionately hard. The Florida Star, a weekly newspaper in Jacksonville, routinely printed a “Police Reports” section describing crimes currently under investigation. One report included the name of a sexual assault victim. This violated the Star’s publication policy (an ethical problem) and a state law prohibiting the disclosure of sexual assault victims’ names. She sued, and the trial court awarded her $75,000.

The United States Supreme Court disagreed. The court held that the newspaper staff hadn’t broken any laws to obtain the information, so punishing them for printing it violated the First Amendment.

Making the Digital Leap

As the demand for printed newspapers declines, newspapers have increased their online presence. Every major metropolitan daily newspaper has a web site, and more and more small newspapers have closed up their print operations entirely and now exist only in “cyberspace.”

The process is proving more difficult than it should be. The standard “formula” for figuring money flow in the print newspaper industry is that the money people pay for subscriptions and single-copy purchases is approximately enough to meet the printing costs (paper, press operators, carriers and so on). Content generation (reporters, photographers, editors and so on) and profits are paid for with ad revenue.

So what’s the problem with moving online? If people access your publication online for free, they don’t pay for subscriptions or copies anymore. But then you don’t have to pay for printing or distribution, so your content and your profits shouldn’t be affected.

Still, newspapers struggle with the profitability of their web sites. Some, including The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, have gone to a “paywall” system that requires readers to pay a fee before accessing part of the online content. Paywalls have some profit potential, but they can also drive readers away. When the Times started charging for content, I quit reading it online. Not that I begrudge fellow journalists the right to get paid for their work, but I do a lot of my online reading with an eye toward creating links to interesting articles and adding them to this Media Survival Guide. So even if I subscribed to the Times, you’d also have to subscribe or you couldn’t follow my links to it. That dramatically decreases the newspaper’s usefulness to you and me both.