I had trouble naming this section of the guide. I ended up going with “Records” because that tied it in with an existing part of the 8sails media-related stuff selections. But in a way the term is outdated, because traditionally it refers to LP records pressed on vinyl, a technology largely replaced by CDs way back in the 1980s.

“Recordings” might have been more comprehensive and accurate. But then the word was basically “records” with an extra syllable.

“Music” was the next term that came to mind. It’s likely to be the most ancient of all arts, and it makes up the lion’s share of this medium today. But not all of it. Spoken word recordings may not account for the majority of downloads, but they’re still an important part of the recording industry.

Whatever the name, the subject is the same. Musical or not, recorded sounds play a big role in the U.S. media infoscape.

The First Recordings

Early attempts to record sound were less than successful. Actually, to be completely fair, in the early 19th century scientists figured out how to transform sound vibrations (actually small changes in air pressure) into ink marks on a roll of paper. Trouble was, ink marks can’t be played back.

In 1877, Thomas Edison came up with a device that would not only record sound but play it back as well. His Phonograph made scratches on a tinfoil-coated cylinder, and when the process was reversed the scratches were amplified back into audible sound.

Edison’s system worked just fine for what he wanted to do with it: record messages for limited playback, such as bosses dictating letters for typists. But because the system used a cylinder, records couldn’t be copied. This prevented the Phonograph from becoming a mass medium.

Emile Berliner’s Gramophone solved the mass production problem by recording onto a disc rather than a cylinder. The basic “scratching” technology was the same, but once sound was recorded on a master disc it could be turned into plates and reproduced over and over again.

Thus the recording industry was born.

Rock n’ Roll’s Original “Drag Queen”

Richard Wayne Penniman – better known to the world as Little Richard – has been named one of rock and roll’s best singers. His compositions and vocal style were vital to the creation of the new music style in the 1950s. Odd, then, that early on the most popular versions of his songs weren’t his.

He climbed a fair way up the charts with songs such as “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally.” But at the time racism was a strong limiting factor in the careers of many performers. Many white parents wouldn’t permit their kids to listen to “black” music. Some white musicians took advantage of this prejudice by doing “covers” of songs by black artists. Pat Boone and Elvis Presley both had more success with Little Richard’s songs than the composer himself.

On the other hand, Little Richard had at least one advantage over many other black male performers at the time: his androgynous appearance. He tended to appear on stage wearing brightly-colored clothing, outlandish hairdos and a considerable amount of makeup. Parents in the white suburbs who feared interracial dating weren’t as worried about Little Richard seducing their daughters.

The King of Rock n’ Roll

Elvis Presley was the music industry’s first genuine superstar. There had been plenty of popular performers before Elvis, but nobody with his style, charisma or instant recognition.

His life as a professional singer began in 1953 when he was discovered by Sun Records producer Sam Phillips. His early recordings were blues and country songs, but they featured an upbeat rhythm that set them apart from what most other white artists were doing.

By 1956 he was a national sensation with a string of hits including “Don’t Be Cruel,” “Love Me Tender” and several other tunes still familiar today. His gyrating performance style upset parents, wowed fans and earned him the less-than-creative nickname “Elvis the Pelvis.”

His career got sidetracked when he did a two-year tour of duty in the Army. And while other musicians transformed the industry in the 1960s, Elvis’s manager Tom Parker booked him into a long series of movies. Though he made a comeback in the late 60s and early 70s, he was never again the earth-moving pop culture phenomenon of his younger days.

Elvis still holds several music records, including most Top Ten hits (with 38) and most weeks at number one (80).

Stop! In the Name of Love

By the mid 1960s, black performers were finally finding their way into popular culture. Detroit-based Motown Records created a new, unique sound – not as frantically up-tempo as most rock n’ roll at the time – that captured national attention.

The label broke further ground in 1961 by putting its best writers behind The Supremes, an all-female trio (Diana Ross, Florence Ballard and Mary Wilson). After a rocky start or two, the group started climbing the charts in 1964. In the following year the Supremes had a record-setting string of number one hits, including “Stop! In the Name of Love” and “Come See About Me.”

The Supremes’ success in 1965 was particularly noteworthy because of their “Motown sound” success in the middle of the “British Invasion,” when music of an entirely different style generally dominated the charts.

The trio survived some hard times touring on bus caravans, but it eventually came apart over internal problems. Ross, the group’s stand-out star, left the group in 1970 and went on to a successful solo career in music and movies. Wilson managed to keep the Supremes going with other singers for another seven years before disbanding and retiring the name.

All You Need Is Love

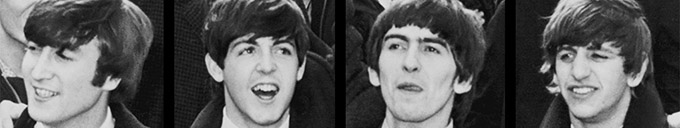

Prior to 1964, American musicians dominated the American music market. Beatlemania changed all that.

The Beatles started small, playing clubs in their hometown of Liverpool, England, and then Hamburg, Germany. The band was originally formed by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who were joined by George Harrison. After two or three other performers came and went, they settled on Ringo Starr as a fourth member. Manager Brian Epstein picked them up as a client in Germany, cleaned up their image a bit and helped make them a big success in Britain.

From there they formed the vanguard of the British Invasion, a period of immense popularity for English groups in the United States. The group won the hearts of American audiences with cheerful numbers such as “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Can’t Buy Me Love.” Their conservative suits, “mop top” haircuts and quirky personal styles made them an appealing combination of safe and rebellious, perfectly suited to the mood of the time.

And as the times changed, the Beatles transformed as well. Their late 60s music reflected the anti-war, pro-drug Hippie counter-culture. In 1966 they gave up touring, focusing on studio work and experimenting with new music techniques and Eastern philosophy.

By 1970 rifts between band members broke the Beatles up, but all four went on to successful solo careers.

The Man in the Mirror

Michael Jackson began his musical career at the ripe old age of 11, singing lead for his brothers in The Jackson 5. If he’d never done anything else, this early work for Motown would have made him a star.

But he became a genuine pop culture phenomenon after teaming up with record producer Quincy Jones. Their first collaboration – Off the Wall – established Jackson as a solid solo act. But his next record made history.

Thriller included no less than seven songs that made it to the top ten. It remains the best-selling album of all time. It also paved new ground in the growing market for video music. Jackson became the first black performer to get regular play on MTV, and his video for the album’s title track was shown over and over again even though the full version was more than 14 minutes long.

That alone would have cemented his spot in the history books. But he went on to many other successes, such as co-producing the USA for Africa “We Are the World” hit, starring in Captain Eo, a movie attraction at a Disney theme park, and releasing several more highly successful records.

His fame brought his personal life under close scrutiny, leading to accusations ranging from plastic surgery addiction to child molestation. But after his death in 2009, his musical legacy has endured.

I Wanna Be Sedated

By the middle of the 1970s, popular music hit a rut. Many people – critics and ordinary listeners alike – felt that the industry had become self-indulgent (not unlike society as a whole), churning out empty-headed, over-produced nonsense. So a market developed for a backlash, rock that returned to simple chords and energetic performances.

In 1976 the Ramones paved the way for what was to become the punk rock movement. Some of their songs were covers of old beach songs such as “California Sun” and “Surfin’ Bird.” Many others were originals, such as “Sheena Is a Punk Rocker” and “I Wanna Be Sedated.” But they all had a common beat, simple melodies, and performances that were loud and fast.

The band’s low-key image matched its music. Publicly they were all known by the last name “Ramone” (even as old members dropped out and new musicians were added). They wore tattered clothes and perpetually looked like they needed a shower. Thus they helped create a musical style that was about music rather than image.

The Ramones never once recorded a top ten hit. But then climbing the charts wasn’t really what they were after. Instead, they established a new style of music that continues to influence the industry today.

The Prophets of Rage

Public Enemy didn’t invent rap music, a genre that was pioneered by groups such as the Sugarhill Gang years earlier. But they brought a powerful political message to their work that music rarely matched before or since.

Three musicians made up the core of the group: vocalists Chuck D and Flavor Flav and DJ Terminator X. After opening for the Beastie Boys and releasing Yo! Bum Rush the Show in 1987, the group followed up with It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back in 1988 and Fear of a Black Planet in 1989.

Nation of Millions broke new ground with tracks such as “Don’t Believe the Hype.” Fear of a Black Planet went even farther into radical political themes with songs such as “911 Is a Joke” and “Fight the Power” (which later gained further fame as the opening theme in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing).

Public Enemy was no stranger to controversy. Group member Professor Griff drew criticism for making anti-Semitic remarks, and the video for “By the Time I Get to Arizona” showed a fictional scene of state politicians being assassinated for refusing to recognize the national Martin Luther King holiday. And of course front man Flavor Flav had an embarrassing post-band career on reality television.

On the other hand, Public Enemy’s influence on rap and hip hop is hard to overstate (check the “Legacy” section of the Wikipedia entry for a sample). And their work represents a point in time when the music was designed to motivate listeners to work for change in the world.

Not What You Say ...

Music affects us psychologically in ways that other communication methods don’t. Audio input – especially the carefully arranged sounds found in musical compositions – can bypass our conscious thought processes and go straight for our emotions. You can experiment with this effect by selecting the “isolated score” audio option available on many DVDs and focusing on how the movie’s music manipulates your reactions to what you’re seeing on the screen.

At least as far back as the Ancient Greeks, philosophers recognized the power of music. In The Republic – Plato’s famous book about the creation of an ideal society – Socrates muses about what music should and shouldn’t be allowed. His concerns seem odd to modern readers, because he focuses not on the message of music but on the way the notes are put together. Some composition schemes would be allowed, he said, while others would be banned.

Plato’s approach has relatives in the 21st century. Some of rock’s detractors earnestly believe that the music’s rhythm is designed to open listeners up to evil forces. Critics such as Jack Chick argue that even Christian rock with Christ-centered lyrics is still evil because the underlying beats put demons in your soul.

However, we don’t have to go to religious extremes to find evidence that music’s lyrics aren’t always as important as the notes and beats. Research indicates that listening to songs can trigger biochemical reactions in the body such as the release of dopamine to the brain (the same thing that happens during other potentially addictive activities such as sex).

Records

For the first hundred years or so of the music industry’s history, sounds were recorded for playback on grooved discs. Although the underlying technology changed little from the days of Emile Berliner until the 1980s, the industry did try several variations on the record theme.

The first format in widespread commercial use (starting around 1900) was the 78, so called because records rotated 78 times per minute. The grooves where the sounds were recorded were larger than systems that developed later, so even a relatively large record (with a ten inch diameter) could only store roughly three minutes of music per side. Further, records were made from shellac, which made them stiff and brittle.

In the late 1940s, two different systems developed at more or less the same time. RCA developed the 45, a smaller (seven inch) format that like the 78 had room for only one song (or two if you count the “B side”). These were ideal for juke boxes, because the machine could easily select and play whatever tune had been ordered. They also fit well with marketing systems such as “Top 40,” which followed the popularity of single songs.

On the other hand, CBS came out with the Long Playing record, also known as the 33. LPs were larger (12 inches) and rotated slower, so they could hold 20 to 30 minutes of music per side. Artists using this “album” format had to create sets of songs rather than just a catchy single.

Both of the new formats played records made of vinyl, which was more flexible and harder to damage (though they could still be scratched and rendered unplayable with careless handling). And both formats remained in common use until replaced by the CD in the early 1980s.

Audiotape

At the height of World War Two, Allied intelligence had a problem on its hands. They’d been monitoring radio broadcasts out of Germany and noticed something strange. When a prominent Nazi official made a speech, it was broadcast over the radio (no surprise there). Later it would be rebroadcast from stations in other parts of the country (again no surprise). However, the rebroadcasts were so close together that they couldn’t possibly be the same person giving the same speech in different cities. And yet the audio quality was so clear that it couldn’t possibly be a recording. Intel analysts concluded that the Nazis were employing voice doubles, actors who sounded just like government officials, to re-read the speeches for different radio stations.

The Germans were actually using magnetic tape, a technology the “good guys” hadn’t developed yet. Tape recording was entirely electronic, so it lacked some of the clicks and pops of the older mechanical disc recording systems. In addition to improved audio quality, tape also offered other benefits such as ease of editing, with mistakes simply snipped out and the tape with only the good parts spliced back together.

After the war the United States seized this new technology and swiftly put it to use back home. At first it did duty primarily in recording studios, but eventually consumer formats such as the cassette tape hit the market. Cassettes were popular because people could make their own “mix tapes” by recording their favorite tracks from albums, and they were skip-proof for cars and other out-of-home uses.

Even after digital audio replaced tape for most personal uses, it continued to be used in recording studios because of the high quality audio that could be stored on it.

Compact Discs

For the first century or so of its history, the recording industry used analog technology. Analog systems record sound vibrations directly, storing them as scratches on a disc or magnetic fluctuations on a tape. But in the 1970s, engineers began work on a new, digital means of recording and playing music. The new technology converted sounds into binary code, which could then be decoded by a player and turned back into sound.

Sounds like a lot of trouble, right? Why not just record sound directly rather than adding a lot of complicated encoding to the process? Because digital information could be stored on compact discs.

CDs offered several advantages over older systems. In particular, they were smaller than older systems. An entire LP’s worth of music (and then some) now fit on a disc smaller than a 45. The new discs were also harder to damage. They weren’t as easy to scratch as vinyl records, and they didn’t snag or accidentally get erased like tapes.

In 1983 CD players and discs hit the U.S. market. At first they were too pricey for most consumers (especially as many people already had music collections on record or tape). But eventually they started to catch on, especially after CD players became standard equipment in cars and computers.

An economic principle called economy of scale – basically the more you sell, the less you have to charge – helped drive down the price of CD players in the 1980s, thus making the new format more popular. But the same principle failed to drive down prices of the discs themselves. Record companies kept the prices the same even as costs decreased, which of course increased their profits.

MP3s

Once songs could be stored as digital information on discs that could be played in computers, it was only a matter of time before the “middle man” got cut out. In the 1990s a method of digital compression called Moving Pictures Experts Group Audio Layer III – MPEG Audio Layer 3 for short or MP3 for even shorter – saw a big surge in popularity. Using free software, users could put audio CDs in their computers, convert the songs to MP3s and save the files on their hard drives.

The conversion process involves “lossy compression,” a system that reduces data by “simplifying” recordings. This compression causes a loss in audio quality. For many purposes – such as playing over the bad speakers in my noisy Jeep – the difference isn’t significant. But when played over a high-quality sound system, MP3s don’t sound anywhere near as good as uncompressed music.

Once MP3 use became common, two things happened almost immediately. First, when “burnable” CDs hit the market, people could make their own mix discs. But another, less above-board practice also arose: downloading. Because MP3s were data files, they could easily move from computer to computer. File sharing systems such as Napster allowed users to download vast collections of songs without paying a dime for them.

Though the music industry fought hard against illegal downloads (more on that later in this chapter), it couldn’t un-invent MP3s. Downloading forced the record companies to make radical changes in the way they do business.

Decline and Reinvention

For decades being a music company executive was one of the world’s sweetest deals. The “Big Six” – EMI, CBS, BMG, MCA, Warner and PolyGram – were among the world’s most profitable businesses.

Music downloading set the whole industry on its ear. As any Economics 101 student can tell you, artificially inflated prices tend to lead to the development of a black market for goods. So when record companies converted the economy-of-scale savings in CD production to extra profits rather than less expensive CDs, they set the stage for what happened once illegal downloading became easy to do.

The bottom dropped out of the business almost overnight. In 1999 the industry was taking in approximately $14.6 billion per year in the United States. Nine years later, that figure was down to $10.4 billion. The Big Six became the Big Three: Sony, Warner and Universal.

Nor were the big labels the only victims. Online music distribution via direct services such as iTunes and CD sales from online retailers such as Amazon drastically reduced the need for “brick and mortar” music stores. Even large chains such as Tower Records found themselves bankrupt.

The business models emerging from the ashes are more complex than the old sales schemes. For years most sales centered on albums, sets of music on LP, cassette tape or CD. They were neat little bundles with more-or-less standard prices. They came in standard sized packages with art on the covers.

Now, however, listeners have the option to download single songs rather than entire albums. Direct online sales don’t require standard packaging, pricing, album art or a lot of the other longtime staples of the music industry. These changes have posed a host of questions the big labels are still struggling to answer.

Licensing

Music ownership starts simple. If you compose a song, you own it. You have the right to sing it whenever and wherever you want, and you have the right to get paid for your performances. But what if you want to sing a song written by somebody else? Or if somebody else wants to sing a song you wrote? Or play a recording of your song at a party or on the radio or on the soundtrack to a movie?

If every individual composer and performer had to strike separate deals with everyone out there who wanted to play their music … well, the agreements with radio stations alone would swiftly turn into a licensing nightmare.

Fortunately, Performance Rights Organizations (also known as royalty agencies) simplify things somewhat. PROs such as ASCAP (the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) and BMI (Broadcast Music Incorporated) serve as go-betweens linking artists with those who want to play their music for profit.

On one side, artists join a PRO and make their music available via the service. Then radio stations, DJs and the like can subscribe to the PRO’s service and get the rights to play the music in exchange for a fee. Of course they have to keep track of which songs are actually being played so the right artists get compensated. And special uses (such as movie soundtracks or ads) typically require special deals.

PROs occasionally stir controversy, such as when ASCAP threatened legal action against the Boy Scouts of America for singing copyrighted songs. But for the most part they do a solid job at making sure users pay and artists get paid.

DRM (or why I don’t trust iTunes)

A few years back I was getting up to leave the theater at the end of Lord of the Rings: Return of the King when I noticed a familiar voice on the soundtrack for the end credits. I’ve been a fan of Annie Lennox’s work ever since her days with the Eurythmics, and I liked the song she did for the movie. My usual 20th century mindset was to buy the CD for whatever music I wanted to own, but in this case I didn’t want the whole soundtrack album, only the one song. So when I got home, I got onto iTunes and spent a buck for the song I wanted.

That’s when the trouble started. Or to be more precise, the trouble started eight years later when the hard drive on my computer died. I had a backup of my music (thank goodness), and when I loaded it back onto my new drive I could play all my music from CDs just like before the crash. The stuff I bought from iTunes, on the other hand, was locked up. Every time I tried to play any of it, iTunes asked me for a password (which of course I’d forgotten, as it was stored on the old, dead hard drive).

In this brave new media world, ownership is not what it used to be. In the old days of CDs, when you bought a disc you bought the right to play the music on it. You also got the right to make backup copies (such as digitizing it to MP3s) as long as you didn’t start making extra copies for your family, friends or strangers. But Digital Rights Management changes all that. Now companies can put hidden locks on the music you buy, preventing you from making illegal copies but at the same time also blocking some forms of legal use in the bargain.

Responsible companies selling DRM-restricted media are good about at least disclosing the terms of use up front rather than burying it deep in the fine print of user agreements or failing to disclose it at all. But some critics charge that even a well-publicized DRM lock is still a problem. After all, why should the simple act of buying a copy of a song be more than a low-involvement purchase?

In the corporate world

As you’ve probably already gathered by reading this far, the recording industry is in a state of transition. However, some of the basics of the business are likely to remain unchanged.

Songs will still have to come from somewhere, so there will still be a demand for the people who write them (composers) and the people who sing and play them (performers). And of course making recordings (no matter how they eventually get to the public) still requires producers and studio professionals.

Artists who don’t handle their own distribution often end up signing with a record label, either one of the large corporations or one of the many independents in the business. On the label’s side, A&R (Artist and Repertoire) people scout new talent and serve as liaisons between talent and the company. The distribution process also requires several kinds of marketing professionals (package designers, public relations people and the like).

Starting a Band

As a responsible adult, one of the things I’m probably expected to do is try to talk you out of trying to break into the music industry. “Sure, start a band in your garage,” I should say. “Just make sure you have a backup career in mind in case it doesn’t work out.” Strongly implying, of course, that you aren’t going to make it.

That’s probably good advice. But if you’re going to try it anyway, go for it. Just understand what you’re getting into.

As far as your chances of success, you should have a better grasp of that than I do. In general, if you and your bandmates lack skill and talent then your chances aren’t good. Objectively, if you aren’t devoting a lot of time and energy to developing your craft, that’s a good indication that to other people (such as A&R pros who might sign you with a label) you aren’t going to sound like you’re serious.

Even if you do turn out to be good enough to make it, you still need to understand the limits of working for a record label. In particular, don’t be surprised when the profits from your recordings don’t turn out to be what you expect. From the $16 price tag on a typical CD, the label will keep somewhere around $5 as profit. Most of the rest of the money will go to other parts of the business (distribution, retail and so on), often leaving you with a dollar or less. And even that will be cut by the label’s demand that you pay back any money advanced to you for recording costs and the like. You may also be required to place some of your money in an advance fund to cover the expenses of your next album. After everyone else gets done eating, your slice of the pie can be as small as 40 cents.

Backmasking

One of the most persistent urban legends in the music industry is that musicians use “backmasking” to hypnotize their fans into worshipping Satan or killing themselves. The rumors claim that messages recorded backwards in songs can be picked up subconsciously by listeners, who get brainwashed into doing whatever the backmasking tells them to do.

Backmasked messages take a couple of forms. In some cases, bands deliberately incorporate backwards messages into their music. For example, The Bloodhound Gang included a backwards playing of the words “Devil child will wake up and eat Chef Boyardee Beefaroni” in one of their songs, most likely as a joke.

In others, however, lyrics that sound like normal speech can end up sounding like something else when played in reverse. One of the strangest backmasking accusations was made against the theme from the Mr. Ed Show (a goofy sitcom from the 1950s and 60s about a talking horse). Rumor held that when the theme was played backward that the words “This song is sung for Satan” could be heard.

Whether intentional or accidental, evidence does not support the notion that the human brain can decode backmasked words or that such messages have any effect on listeners. Though artists might face a slight ethical concern about upsetting listeners by backmasking, critics who accuse backmaskers of being Satanic brainwashers face a much more serious ethical problem.

The Washington Wives

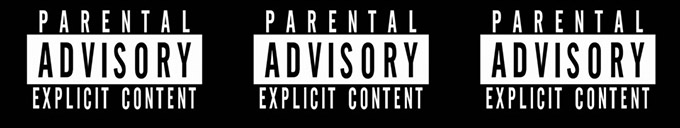

Back in the mid 1980s, the federal government lashed out at the music industry. Actually, it wasn’t the government itself. Rather, it was a group of four women who were all married to prominent politicians. The group, informally known as the “Washington Wives,” was officially called the Parents Music Resource Center.

Led by Tipper Gore, wife of then-Senator Al Gore, the PMRC alleged that popular music trends were responsible for social decay, particularly the disintegration of the traditional “nuclear family.” The group came up with a “Filthy Fifteen” list, a set of songs it claimed had lyrics that were unsuitable for younger listeners due to references to sex, violence, drugs, alcohol or the occult.

In response to the PMRC’s pressure, several record labels agreed to adopt a content warning system akin to the ratings used for movies. But before the system could be put into place, the Senate held a hearing on the subject of indecent music (despite the government’s complete absence of authority to censor song lyrics). The hearing drew a lot of publicity when musicians as different as John Denver and Frank Zappa appeared to testify against government-mandated labels.

The industry adopted the PMRC’s black and white “Parental Warning – Explicit Lyrics” stickers as a self-regulation system. The “Tipper sticker” was supposedly designed only to warn parents about albums with potentially indecent songs. However, the system turned into economic censorship when several retailers such as Wal-Mart refused to carry albums that bore the sticker. On the other hand, some musicians regarded the stickers as badges of honor, not to mention a good way to attract listeners looking for less mainstream music.

As Nasty as They Wanna Be

Thanks to the First Amendment, in the United States most music censorship is economic (such as when stores refuse to carry music with risqué lyrics) rather than governmental (other than FCC restrictions on radio play, that is). Thus a sheriff in Broward County, Florida, caused a controversy when he warned local music stores that they could be prosecuted for selling an album, As Nasty as They Wanna Be by 2 Live Crew.

The album included a song – “Me So Horny” – that the sheriff claimed was a violation of the state’s obscenity law. After a federal judge declared the song legally obscene, music store owner Charles Freeman was arrested for selling a copy to an undercover police officer. Then three members of the band were busted for performing the song in a nightclub.

The performers were acquitted at trial, at least in part because Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates testified that the band’s lyrics had legitimate roots in African-American musical traditions. Freeman was convicted, but his conviction was overturned on appeal based on the Constitution’s protection of free speech.

The controversy primarily served to popularize the album, which climbed to number 29 on the Billboard chart.

The RIAA vs. Listeners

Copyright violation is both a crime (for which you can do prison time) and a tort (for which you can be sued). On the lawsuit side, the music business’s champion is the Recording Industry Association of America, a trade organization that aggressively drags violators to court.

The RIAA is particularly serious about suing people who download illegal copies from the Internet. Though criminal prosecutions are generally limited to large-scale, for-profit operations, the RIAA has been known to sue even individual downloaders. In 2006 the association filed hundreds of lawsuits against small-time “thieves.” And as each illegally downloaded song constituted a separate violation, defendants got hit with judgments stretching into the millions of dollars.

Despite this aggressive stance, however, the practice still continues. One European industry group estimates that 95% of all music downloads are illegal. Further, some musicians are actually in favor of the practice, observing that downloads are a way for new bands to capture listeners’ attention.

Musicians vs. Musicians

Copyright problems also arise between musicians, usually as a result of a practice called sampling. Some artists create compositions that use samples – small pieces – of songs by other performers. This practice has led to no end of in-court arguments about how much is too much.

The law creates a “fair use” exception to copyright for some limited uses. One of the standards used to determine whether or not the exception applies is the amount of the original work used in the copy. Copying an entire song wouldn’t pass the test, but using just a few notes may be another matter.

Sampling creates ethical as well as legal concerns. When Vanilla Ice sampled “Under Pressure” by Queen and David Bowie, he stirred a controversy by refusing to acknowledge that his use was a sample. Critics also attack songs they claim don’t have much original musical merit beyond the use of a sample from a better piece of music.

Musician vs. musician ownership problems aren’t limited to sampling. They can crop up anytime some doubt exists about who actually created what. One of the stranger cases was TV producer Gene Roddenberry’s decision to write lyrics for the theme music for the original Star Trek series. Though the lyrics were never actually used (good thing, because they were purely dreadful), Roddenberry was nonetheless entitled to half of all the royalties that would otherwise have gone entirely to composer Alexander Courage.

And former Credence Clearwater Revival singer John Fogerty found himself in court for stealing a song he wrote. His work for CCR legally belonged to label owner Saul Zaentz, so when Fogerty went solo and later wrote a song called “Old Man Down the Road,” Zaentz claimed that the melody was a reheated version of CCR hit “Run Through the Jungle.” Though the jury concluded that the two songs didn’t sound that much alike, Fogerty still had to go through the hassle of being sued for stealing a song he wrote.