This is one of the shorter chapters in the Survival Guide. At least in part the lack of length is due to the lack of history. Unlike books, movies and the other older topics, social media hasn’t been around all that long. “Journey back with me now to the thrilling days of 2006” doesn’t make much of a start to a story.

Further, this new medium isn’t as well established as the rest. At this point in media history we have a pretty good idea who the major players are, where they came from and how they work. Even with media in transition (such as recordings and newspapers), their origins help us understand what’s going on with them now.

We’re still in the “origins” phase of social media’s development. Though I can make reasonably reliable guesses about the success or failure of some sites, many more stand an equal chance of thriving or dying. So if you follow the Survival Guide on a long-term basis, you’re likely to see this chapter change a bit in the coming years.

But please don’t mistake shortness of text for lack of importance. In some ways social media are the most important topic in the book. They blur the lines between mass communication and interpersonal communication. And that’s not just textbook trivia. This blurring of distinctions may have a major impact not only on social media sites themselves but also on the media industry as a whole.

Geocities

Everybody wants her or his own web site. We can all think of something we can use the web for, whether it’s publishing a major metropolitan daily newspaper, distributing information about the mass media in “survival guide” form or just sharing photos of the kids.

Creating a web page isn’t the world’s most difficult task (if I can do it, anyone can do it). Even back in the day when page creation required HTML coding, it still wasn’t a prohibitively difficult task. However, “web presence” became an option for literally everyone starting in the mid 1990s thanks to Beverly Hills Internet.

BHI established a web site called GeoCities. Anyone who wished to could set up a page on the site free of charge. Pages were organized into “neighborhoods” according to interest (Wall Street was for financial pages, Hollywood was for entertainment interests, and so on). Individuals who set up pages were called “homesteaders,” almost as if they were setting up actual, physical addresses in real cities.

The site proved immensely popular. By 1997, just two years after it was founded, GeoCities became the fifth most popular site on the web and added its millionth homesteader.

Sadly, just two years later Yahoo! purchased the site and shut it down. The closure occurred so rapidly that many GeoCities users didn’t get the chance to move their content to other locations on the web. Despite efforts to archive the neighborhoods, many pages disappeared forever.

Facebook is the current social media champion. The site has more than two billion users who are active at least once a month. If the site was a country, it would be the most populous nation in the world.

After getting off to a rocky start (hacking into college computers to get student ID photos for a Hot-or-Not-ish site called Facemash), Mark Zuckerberg started thefacebook.com, a social media site that at first was limited only to his fellow Harvard students. But it swiftly proved so popular (half the university’s undergrads signed up in less than a month) that Zuckerberg and his partners decided to expand, first to other Ivy League schools, then to other universities, then to high schools, then to anyone over the age of 13 with a valid email address.

So what do billions of people do on this site? The first thing most users see when they sign on is their newsfeed, a stream of posts from the people and organizations they follow with the most recent postings first (more or less). When a user creates her own post, it goes on her wall (a list of her posts as well as things she’s shared from other users). It will also go into the newsfeeds of her friends and the people who follow her. She can also post photos and video.

Who gets to see what is a matter of how account privacy is set up. At the most open level, anyone on Facebook could potentially see a post (especially if the user pays to have it “boosted” onto more newsfeeds). At its most private, Facebook can be used to store things that only the user herself can see.

Because of its popularity, many companies use the site to promote themselves by setting up pages that users can follow. They can also pay for advertising or to have their posts inserted into users’ newsfeeds. If you see something called a “suggested post,” you’re looking at a paid contribution to your Facebook experience.

The site continues to expand and evolve. Recent additions include a marketplace where users can post notices about things they’d like to sell or just get rid of.

Social media doesn’t get much simpler than this. Twitter users communicate with their “followers” via brief (no more than 280 characters) messages called “tweets.”

The original plan for the website was a podcasting platform called Odeo. But when Apple announced that it was setting up its own podcasting service within iTunes (and thus automatically set up on all Apple computers and mobile devices), Odeo decided to change direction.

To start, Twitter was supposed to be a “status update” system. Tweets were short (originally limited to 140 characters) because they were designed just to communicate what you happened to be up to at the moment: “in class,” “on my way to the store,” “making people mad in a movie theater” and so on.

But sometimes technology has a mind of its own. Users swiftly started using Twitter to share random thoughts, links, information that might be of interest to someone besides friends, family and stalkers.

Celebrity tweeters helped quite a bit. Famous folks from Taylor Swift to Donald Trump use the site to keep their fans posted about their daily thoughts and activities.

Bulletin Boards

Social media technically goes all the way back to the days before the Internet (or at least before the Internet became a mass communication medium). In the late 1970s, computers connected to one another using dial-up modems. These devices differed from modern phone-line-based connections in that the “conversation” between the computers was audible (and would tie up the phone line while you used it), it was much slower, and it connected you to only one other computer at a time.

For many home computer users, Bulletin Board Systems were popular modem partners. BBSes were specialized computers designed to work like traditional, dead-tree bulletin boards. Users dialed up the BBS’s phone number, connected, posted information and read what others posted.

BBS systems fulfilled many of the needs that web-based social media cater to today. On a local scale, churches and community groups set up BBSes so members could read up-to-date information and send messages to each other. In places where people were more spread out – such as the Australian outback – users living in remote spots could connect with one another and form BBS communities.

Groups with specialized interests also set up BBS systems, allowing people with diverse interests to communicate. Some even hosted Multi-User Dungeons, early forerunners of multiplayer games such as World of Warcraft.

Of course the Internet rendered BBSes obsolete by connecting thousands – and later millions – of computers all at once.

Usenet

The Internet simplified and sped up connections between computers, providing the hardware backbone to allow every machine on the network to connect to every other machine. Although faster, better communication was now possible, the Internet lacked centralized “bulletin boards” where people could connect with one another.

Enter Usenet. First developed at Duke University in 1980, Usenet was a system of newsgroups resembling a bulletin board. Users connected to the server (later a series of servers) and located groups dedicated to their interests. Usenet was divided into hierarchies (such as sci for science, rec for recreation and so on). Larger sections were divided into subsections, such as rec.sports and then divided further, becoming more and more specialized “newsgroups” (rec.sports.baseball.kcroyals).

Some groups were moderated, which meant that postings from users had to be approved by someone in control of the group before they would appear on the server. Others were unmoderated, allowing everyone to post whatever they wanted (and you can imagine how well that worked in some discussion areas).

Many regular users thought the system took a fatal turn for the worse in September 1993 when AOL made it part of the company’s service, introducing a flood of “newbies” into the newsgroup world. Usenet served as an excellent bridge between older BBS technology and full-fledged web-based social media.

MSG CASE STUDY: CLASS AND CULTURE

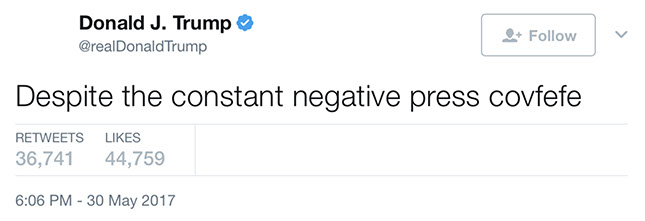

Trump’s Tweets

Donald Trump is the first US President to make extensive personal use of social media, specifically Twitter. His tweets have changed the relationship between the presidency and the people.

Presidential use of media innovations is nothing new. Roosevelt used radio – via “fireside chats” – to build support for his social programs. Kennedy’s TV-friendly appearance helped him win the narrowly-decided election in 1960. But Trump is the first President who’s ever used social media for direct, 24/7 access to the infoscape. For better or worse, he has changed the way the President communicates with the nation and the world.

Results have been mixed. Many of his tweets are simple what’s-on-my-mind messages, which capture public attention only when what’s on his mind happens to be something unpleasant. Often his vitriolic messages become news stories that distract from coverage of more important matters.

But his tweets become more troublesome when he communicates something he shouldn’t have. For example, a remark he made on Twitter about the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election suggested that he obstructed justice by firing FIB Director James Comey. One of his lawyers took responsibility for the tweet and claimed it was a mistake.

And he gave critics and talk show hosts material for mockery when he finished a tweet by typing “covfefe.” Of course anyone can accidentally hit the “send” button too soon. But he didn’t immediately follow up with an “oops, what I meant was” message.

Youtube

Here’s a rarity in the world of social media: a site that does exactly what it was originally designed to do. From its origins in 2005, YouTube was set up to be exactly what it is: a massive online collection of user-posted videos.

In less than a year the company went from a small office in a garage to a $1.65 billion buyout by Google. After all, what’s not to love? An audience of millions can watch videos for free. Users can make their videos available to an audience of millions. And the web site rakes in ad revenue without paying for content.

Of course the plan isn’t flawless. Videos require more computer memory than text files or still images. And of course some users post copyrighted content they don’t own, which has to be removed when it’s reported.

Still, in an average 65 days YouTube users add more hours of content than the four major broadcast networks have created in the last 65 years. It isn’t all footage of a kid biting his older brother’s finger, either. Many professional video producers distribute their products via YouTube hoping to either earn money from them directly or using them to build a market for another product (such as a singer’s music videos helping sell new tracks).

Astroturf

Democracy forces politicians to at least pretend to care about what voters think. In the pre-Internet world, public opinion could be hard to assess. Mail from angry constituents were often a better gauge of what extremists thought than what the majority believed, and polls weren’t always much better.

Social media provided a partial answer. Because it allows “ordinary folks” to publish their opinions, sites such as Facebook allow direct communication between candidates and the public. As most social media sites are free, a politician in the 21st century would have to be crazy not to use them.

To be sure, the system isn’t without problems. Not everybody uses social media, so they aren’t the perfect way to communicate with the whole world. Elected officials may still get more messages from the extremes on an issue than from the general public, particularly if the issue is of great concern to limited groups and little concern to anyone else.

Further, what may at first seem like a “grass roots” movement can turn out to be “astroturf,” an effort by a pressure group or public relations firm to make their message look bigger than it is by using tricks such as creating fake identities.

Blogs

The origins of social media technology are pretty much the same as the tech origins of the rest of the Web. So let’s dive right into how they work.

A blog is sort of a diary (literally “weB LOG”) that anyone can read. They require almost no technical skill at all to establish or maintain, so anyone with an Internet connection can be a blogger. Further, you can blog about anything you wish. Your blog might be about what you have for dinner every night, how much you love (or hate) romantic comedies, literally anything you can think of.

Software such as Blogger make it easy to generate entries, upload photos, audio, video, links and other material. You can even “monetize” by allowing the host site to run ads on your pages, though of course getting paid depends on your blog’s ability to attract readers.

Thus the main question you need to ask yourself before starting a blog is “what do I want to do with it?” If you just want to swap stories with a handful of friends, your chances of success are pretty much 100%. On the other hand, if you’re trying to get a blog to pay enough that you can quit your day job, you’re going to have to come up with something that people want to read about and can’t get from the millions of other blogs out there.

YouTube’s technology

Video is trickier than words. Anyone who can type an email message can blog or tweet, but creating a “moving picture” – even a 30-second clip – requires a bit more technical know-how.

If your ambition is no greater than a few seconds of your dog catching a Frisbee, all you need is a smart phone with video capability and a YouTube account. Use your phone to record Rover making that perfect midair catch, select the “upload to YouTube” option, and your aerobatic pet has the same potential audience as the latest Taylor Swift video.

Please note that I said “potential.” Obviously celebrities have huge promotion staffs and budgets at their command, which you probably don’t. On the other hand, you can increase your video’s chance of getting noticed by giving it a descriptive title and selecting keywords that viewers might use to search for stuff like yours.

The next step beyond dog-and-a-cell-phone videos is to shoot more than one clip and edit them together into something more elaborate. This requires editing software. You can do some basic functions (such as rotating or changing to black and white) within YouTube. But editing clips into sequences the way the pros do requires stand-alone software. I used to be a big fan of iMovie back when it was simple and came free with the purchase of a Mac. But with its typical concern for customers’ needs, Apple changed the way the program worked and started charging extra for it. Though they gave up on the extra charge, the new system still seems strange to me compared to the old one.

MSG CASE STUDY: Global Media

Gangnam Style

In 2012 a South Korean musician named Psy made a surprise appearance on the world stage. Though he was previously little known outside his home country, the video for his song “Gangnam Style” rocketed him to international stardom.

The strangest part was that there was no apparent explanation for it other than the appeal of the YouTube video itself. Though it seemed no different from hundreds of other K-pop tunes, something about it captured attention throughout East Asia. From there the phenomenon spread to the rest of the world.

“Gangnam Style became the first YouTube video to get one billion views. On the way up it passed “Baby” by Justin Bieber featuring Ludacris, a video by an established star supported by a major label. Thus it proved that viral marketing and the global media marketplace were forces to be reckoned with.

Facebook’s technology

Facebook can be as simple or as complicated as you want it to be. You can spend five minutes a day touching bases with your friends or waste hours playing a selection of hundreds of games.

When you establish a presence on Facebook, the system sets you up with a “wall.” This is a space where you can post your thoughts, share links and so on. Anyone you “like” (they’ve accepted your friend request or vice versa) can see what you post. You can also share information about yourself (where you work, where you went to high school and so on) via your profile.

The more you share, the more “clues” you give the Facebook system about how to connect you to other users. After I entered my high school and year of graduation, I was swamped by recommendations from Facebook about other users I might want to “friend.”

The system provides several advantages over email, not the least of which is that you can send information out to a lot of people at once without worrying about address list maintenance or spam filters. On the receiving end, you can “unfriend” someone who’s getting on your nerves or simply “hide” them so you don’t see their posts anymore. I’ve found that particularly helpful with folks who do a dozen posts a day about the progress they’re making in their online games.

Facebook is also something of a microcosm of the web as a whole. Just about every interest you can imagine has a Facebook page devoted to it. Some of them are frivolous, such as “can this dog with a tinfoil hat get more Facebook friends than Glenn Beck?” Others seriously appeal to a limited audience. I’ve found Facebook pages for just about everything from my favorite fried chicken restaurant to a Japanese TV show I watched when I was a kid.

Social media site profits

The standard business model for social media sites is based on advertising. People use the sites for free, but the pages they look at include ads that supply the sites with revenue.

Thus the more people use the site, the more pages on the site get viewed. The more pages that get viewed, the more ads get seen. And the more ads that get seen, the more ads get paid for.

However, there’s economic value to social media even beyond advertising. By signing on and communicating with friends, users provide social media sites with millions of pieces of information about who’s talking about what. Databases of such consumer information have tremendous potential value to marketers.

So even if a site doesn’t make money by making you look at ads, your online activity can still help them pay the bills.

Marketing via social media

As social media increases in popularity and other media lose audiences, marketing pros are paying more and more attention to the potential of sites such as Facebook to get persuasive messages to potential customers.

These 21st century promotional techniques aren’t as simple or as straightforward as their 20th century ancestors. If you watch a TV show, the ads are buried right in the middle of it and can be difficult to avoid. Likewise when you’re reading a magazine, the ads might be fairly easy to ignore but they’re nearly impossible to avoid.

Not so on social media. Ads on the sides notwithstanding, people look at only what they want to see. The trick, then, is to go beyond what you want people to read about your product and give them something they actually care about. It isn’t enough to set up WidgetCo with a Facebook page and hope people check it out. The company needs a gimmick, something like “WidgetCo Presents This Day in History.” If people come to you for something they actually want to read, they’ll associate it with your company.

Blogging for dollars

As a general rule, the site that hosts your blog isn’t going to pay you for writing it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t use a blog to make money. Consider the following four possibilities (and please note that there are other opportunities not listed here):

First, you can advertise. On Blogspot, allowing Google AdSense to stick ads on the sides of your postings is as simple as clicking the “monetize” button and answering a handful of questions about where you want the money to go. Of course the catch is that ads pay based on either page views (how many unique visitors look at your pages) or click-throughs (how many users click on the ads). A popular blog can make some serious cash. But if you only have a handful of readers, best to stick with your day job.

Second, you can use your blog to help you promote something else. If you sew in your spare time, consider mentioning your abilities and your reasonable rates in a blog. Some writers have found success using their blogs to help sell their books.

Third, promote yourself. If you’re an expert on something, you can use a blog to impress people with your knowledge. Then maybe if they need someone with your expertise, they’ll know whom to call.

Finally, some bloggers make money by basically accepting bribes to mention products in their blogs. This was popular for awhile with “mommybloggers,” writers specializing in the interests of new parents. Some of these folks struck deals with the manufacturers of diapers, baby powder and the like to trade favorable mention in the blog for a little cold, hard cash.

Like advertising, you’ll need a good-sized number of readers to pull this off. And you also have to worry at least a little about what might happen to your credibility if your readers find out that you recommended a particular brand of baby food not because it was nutritious or delicious but because you were paid to.

Money for your videos

YouTube is one of the rare exceptions to the general rule that nobody is going to pay you to play around with social media.

First the bad news: you have to come up with a popular video first. Something you upload must either accumulate a lot of viewers all at once or amass a following over time. But once the site records enough views for your work, YouTube may ask you to “partner.” That puts your channel on a paying basis.

More bad news: in exchange for money, the site puts ads in your videos. Usually this takes the form of either a pre-roll (an ad that has to be watched at least in part before your video starts) or a pop-up that appears over your video.

More bad news: it won’t pay much unless you get a lot of viewers. The average amount YouTube pays is $2 per 1000 views.

On the other hand, good news: money. Hey, even $2 is better than nothing. Further, some folks lure in enough viewers to make a serious living at it. Professional-level income usually requires a professional-level commitment of time and expertise. But sometimes an amateur production can hit it big. The “Charlie bit my finger” video – the most popular non-pro video in YouTube history – has drawn nearly 370 million views. That’s more than $700,000 for a parent with a camcorder and a kid who likes to bite his brother.

Mongolian beef robots

Back in the 20th century, reaching an audience of millions (or even high thousands) was an expensive proposition. Before TV stations hired on-air people to speak to a TV-sized audience, they made sure that their potential hires actually knew what they were doing. Even relatively small newspapers offered jobs only to writers with some training and practice.

In 21st century social media, anyone who wants to can publish material that may potentially reach a lot of readers. The thoughts of someone who can barely form complete sentences are just as accessible as the work of seasoned pros. Though this creates some exciting possibilities, it also poses some big problems.

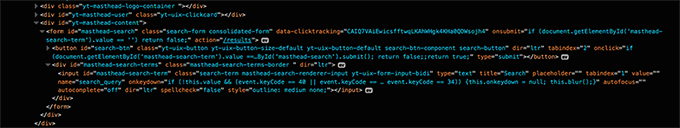

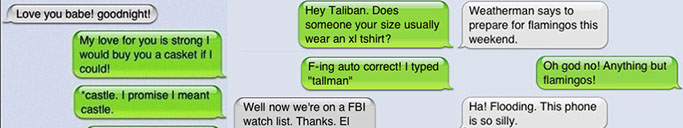

One of the big ones is a little thing called autocorrect. Based on the observation that many writers aren’t the best at spelling and grammar, some software is designed to make fixes for us as we type. This tends to be useful when it simply flags words it doesn’t recognize, an approach that doesn’t eliminate errors but at least helps cut down on them a bit.

Trouble can arise, however, when the software makes changes with little notice to the writer. To be sure, autocorrection can prove useful even with minimal consent. It can also make a royal mess of what you write.

An example from my personal experience: one afternoon I was typing an email to my wife about what we were planning to have for dinner. I offered to cook some Mongolian beef, but I failed to notice that autocorrect added the word “robots” to the end of the sentence. This wasn’t the biggest communication calamity in human history. My meaning was still reasonably clear, and it was just a note to my wife. But a quick search of the Internet will uncover dozens of sites that specialize in listing far more serious mistakes.

Thus one of the first lessons learned by users new to social media is that sometimes the worst mistakes are the ones you don’t even make yourself.

“Nobody knows you’re a dog”

Just about everyone (including me) who writes about social media eventually makes a point about the millions and millions of users. Truth be told, however, nobody really knows how many millions of people are using the sites because nobody knows for sure how many of the millions of users are real people.

To be more precise, many users (nobody really knows exactly how many) use more than one identity. Some even pretend to be someone they’re not, a problem that hits celebrities especially hard.

Fake identities – sometimes known as “sock puppets” – can take several forms, not all of them malicious. One of my friends maintains two different Facebook profiles, one under her real name (making it easy for classmates from high school and other casual acquaintances to find her) and one under a pseudonym (which she uses to communicate only with close friends). Sometimes a fake identity is just for fun, as with a friend of mine who set up a profile for an imaginary rabbit.

On the other hand, false identity can be a more sinister business. In early 2011 two high school students were arrested and charged with multiple felonies for creating a fake Facebook profile in the name of a classmate and posting photos with their victim’s face edited onto another girl’s nude body.

Whether for good or ill, social media sites don’t like fake profiles. They make actual usage harder to track, which in turn makes advertisers less willing to pay for ads. Thus most social media sign-ups require you to promise that you only have one profile on the site. Facebook eventually caught up with my friend with an “acquaintances” profile and an “actual friends” profile and told her she had to get rid of one or the other.

Privacy protection

Let’s start with something that should be more obvious than it is: there’s no such thing as privacy online. If you publish something on the Internet, everyone can see it. Your name. Your email address. Your actual address. Pictures of your kids. Pictures of yourself getting drunk with friends. Pictures of yourself with your clothes off. You post it and it isn’t private anymore.

So the trick lies in knowing what you’re publishing and what you aren’t. You can begin to safeguard your privacy by not posting information you don’t want people to know. For the most part, if you don’t put it up then it can’t leak out. I say “for the most part” because your social media devices may be “telling” on you without your knowledge. For example, some cell phones and tablets will automatically include your location with your messages unless you tell them not to.

Further, hackers occasionally find ways into even highly secure systems. So even information that should be private – such as credit card numbers provided only on secure ordering systems – can end up “leaking.” But try not to get too spooked about this sort of thing. Your credit card is as vulnerable with a server in a restaurant as it is online (something to think about the next time you’re considering being rude to someone in a restaurant).

Privacy is easier to control on some sites than on others. Facebook is particularly notorious for having complicated privacy settings that can make it hard to tell who can see what.

So once again, the overall rule is “don’t put it online if you don’t want everyone to see it.” And if you’re going to risk it, be sure you proceed with caution.

Posting your way to the unemployment line

Celebrities seem to be eternally in danger of getting fired because of their big mouths. Because actors, singers and the like live in a constant spotlight of public scrutiny, an angry word outside a nightclub, a slip of the lip on a talk show or even a simple traffic stop can turn into a career-damaging debacle.

Most of us have the luxury of living outside the realms of such constant attention. Except in one place: social media sites. Here ordinary people are at a particular disadvantage. Rich celebs can hire PR flacks to help keep them from saying something stupid. But the only people who look out for the rest of us online are ourselves.

As a result, a growing number of sad folks have discovered that in many cases employers have the right to fire you even for your after-work conduct if something they don’t like shows up in your social media usage.

Sometimes the problem is something obvious, such as the legendary case of the woman who posted a message on Facebook complaining about her job and calling her boss a “pervvy wanker” (forgetting both that she had two weeks to go on her six-month probationary period and that her boss was one of her Facebook friends). And some companies have no sense of humor at all, firing people for tweeting minor gripes.

In other cases it’s something that seems less like an official company concern, such as “party photos” or even anonymous material about promiscuous sex.

Most employees know that their employers can monitor their on-the-job computer usage. But some bosses routinely do searches of popular social media sites looking for any mention of the company.

YouTube and copyright

Throughout most of the social media world, copyright isn’t a big problem. If you write something, you own it. The same goes for photos you shoot. Links to other people’s web sites are likewise not a problem.

However, problems arise when you start posting things you didn’t personally create. You’re unlikely to tweet anything you didn’t come up with yourself. But in the realm of video creation, sometimes “borrowing” from other people’s work proves more tempting than it should.

Some violations are obvious, others less so. If you digitize an entire music video by your favorite artist and upload it without permission, you’ve violated the law. Uploading just part of another work – such as a single scene from a movie – can still break copyright law. You’re also breaking the law if you use someone else’s work in your own without permission, such as if you make your own music video using someone else’s copyrighted song.

The rules governing copyright are complicated. If you want a simple rule to follow, when in doubt leave it out.

By its nature, YouTube faces the biggest problem with copyright violators. The site has a system in place to deal with violations, removing the offending video and sending the poster to “copyright school.” Serious and repeat offenders can be banned from the site.