Rule of Thirds

I hate teaching about the rule of thirds. It’s a wonderful tool for improving shot composition. But that’s all it is. Still, some students seem to regard it as some kind of mathematical rule, a precise formula that will automatically lead to brilliant photos the way a chemical formula describes a series of reactions with a certain result. That isn’t how it functions.

Nikon D3000, 50mm, 1/1000, F/18, ISO 1600, adjusted

Here’s how the rule of thirds works: our eyes are naturally drawn to compositions that can be divided into three parts. Take this landscape for example.

Nikon D3000, 50mm, 1/1000, F/18, ISO 1600, adjusted

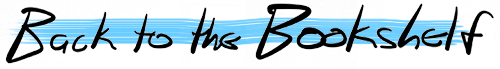

If we literally slice this image horizontally into three parts, the sky occupies the top third and the ground occupies the bottom two thirds. The result is more pleasing to viewers than a composition divided in half, in quarters or by some other measurement.

The principle also works vertically. In this example, most of the graphic weight (the interesting part of the photo) is in the left third of the image.

Nikon D3000, 500mm (150-500mm), 1/125, F/18, ISO 100, adjusted

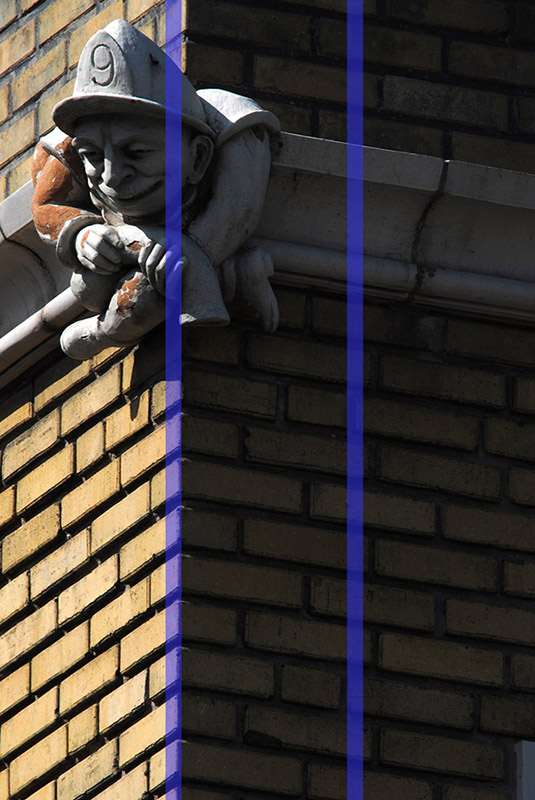

You can also divide a vertical image horizontally.

Nikon D3000, 55mm (18-55mm), 1/60, F/5.6, ISO 200, cropped and adjusted

But use caution. When you divide a vertical picture horizontally and position your subject in only a third of the image, it tends to create a strong lack of balance.

Nikon D3000, 55mm (18-55mm), 1/60, F/5.6, ISO 200, cropped and adjusted

For a photo that feels more stable, consider working with the two thirds mark rather than the one third mark.

Nikon D3000, 55mm (18-55mm), 1/60, F/5.6, ISO 200, cropped and adjusted

Here the rule of thirds is still in use, but the result doesn’t look quite so strange.

Nikon D3000, 55mm (18-55mm), 1/60, F/5.6, ISO 200, cropped and adjusted

Nikon D3000, 300mm (75-300mm), 1/250, F/10, ISO 1600, cropped and adjusted

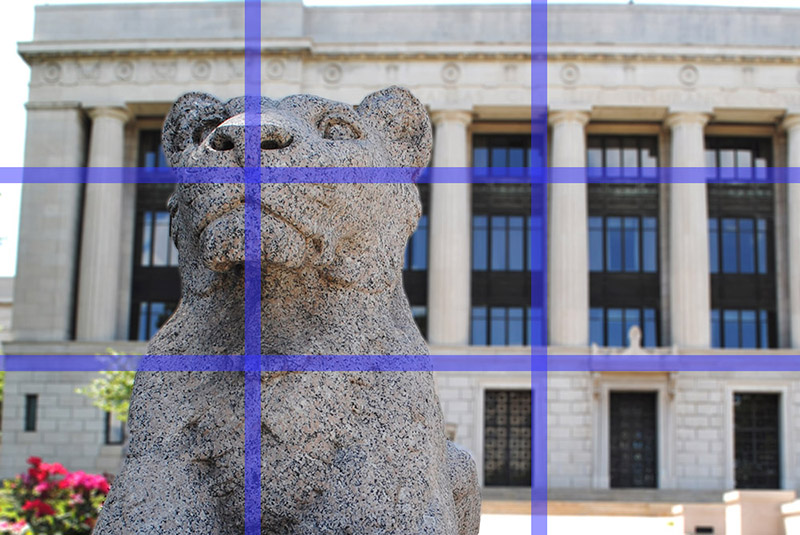

The same guidelines apply to horizontal compositions.

Nikon D3000, 300mm (75-300mm), 1/250, F/10, ISO 1600, cropped and adjusted

A horizontal angle can be divided into vertical thirds. But once again confining the subject to the left or right third throws the balance off. That can be a good thing if you’re after an unbalanced image. But if I wanted something less dramatic when I shot this, I should have tightened in and put the face in two thirds of the shot rather than in the right third only.

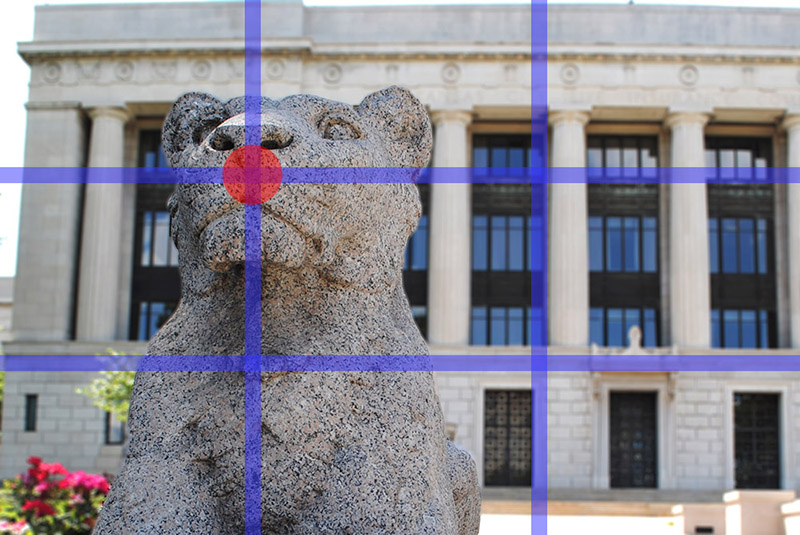

Nikon D3000, 18mm (18-55mm), 1/160, F/6.3, ISO 100, cropped and adjusted

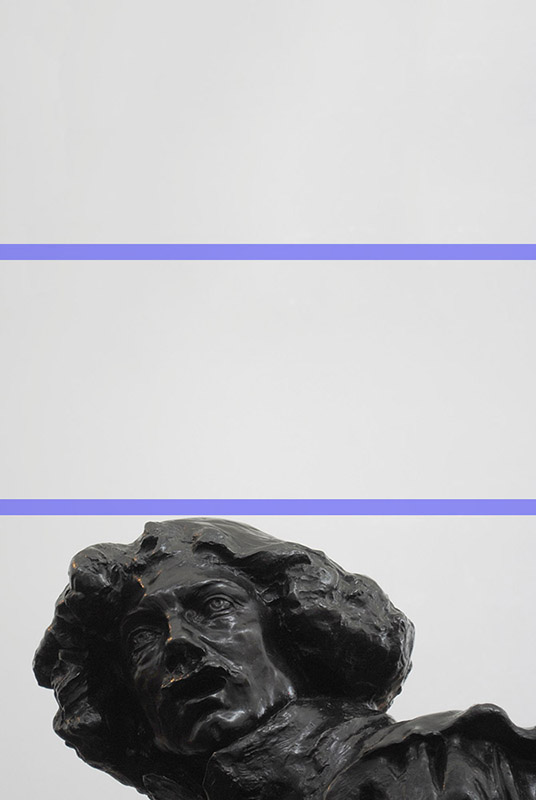

The rule of thirds also has a more subtle variation that can also have a strong, positive effect on your photos. In this example the subject doesn’t appear to be placed precisely in the left third, middle third, or any other third of the shot.

Nikon D3000, 18mm (18-55mm), 1/160, F/6.3, ISO 100, cropped and adjusted

But if we divide the image into horizontal thirds and vertical thirds at the same time, the places where the division lines meet are helpful locations to know.

Nikon D3000, 18mm (18-55mm), 1/160, F/6.3, ISO 100, cropped and adjusted

They’re called power points, and the same visual principles that make the rule of thirds work also draw the eye naturally to these spots in your composition. Note that in this image the subject’s face is centered on the upper left power point.

You can also use more than one power point at once. This is a common technique in portrait photography when the subject is looking straight, face-forward into the camera.

iPhone 4s, cropped and adjusted

The upper two power points sit squarely over the subject’s eyes.

iPhone 4s, cropped and adjusted

Nikon D3000, 26mm (18-55mm), 1/250, F/11, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

I’ll close with the same point I made at the start: the rule of thirds is not a “law of photography.” Plenty of brilliant shots ignore it entirely. However, if you’ve got a composition that somehow doesn’t look quite right, remember the rule of thirds, reframe your shot and see if it helps. If it doesn’t, don’t use it. And if you find your shot literally divided into thirds, you might want to consider using something like the fountain in this example to break things up a bit.