Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is one of the three corners of the exposure triangle. Along with aperture, it controls how much light gets through the lens and onto the recording medium (chip or film) in the back of your camera.

If nothing – neither your camera nor your subject – moves while the shutter is open, fast and slow shutter speeds look the same.

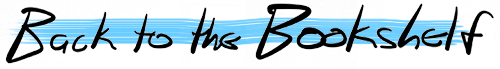

For example, this photo taken of a stationary subject at a shutter speed of 1/320 of a second ...

Nikon D7000, 82mm (28-200mm), 1/320, F/5.0, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

... looks pretty much the same as this shot of the same subject taken at 1/4 of a second.

Nikon D7000, 82mm (28-200mm), 1/4, F/32, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

Note that these photos were taken in shutter priority mode. With this setting selected, you pick the shutter speed and the camera adjusts the rest of the controls to get the light level right. So when I changed from 1/320 to 1/4, the camera compensated by closing down from f/5 to f/32.

But be careful. Hand-held cameras move when your hands do. At slower shutter speeds, camera shake – even the small vibration produced by pressing the shutter button – can make a blurry mess out of your picture.

Nikon D7000, 120mm (28-200mm), 1/8, F/32, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

Camera shake almost always makes a picture look terrible. You can avoid it by increasing shutter speed. I find that a speed of 1/60 or faster generally works for me, though if your hands are steadier than mine you might be able to get away with a slower shutter. If lighting conditions are too dim for a higher shutter speed, lock your camera down on a tripod to keep it from shaking during a slow exposure.

Even if your camera is completely still, a moving subject can still blur your shot. However, motion blur – when used correctly – can actually be a good thing, because it adds a sense of movement to a still image.

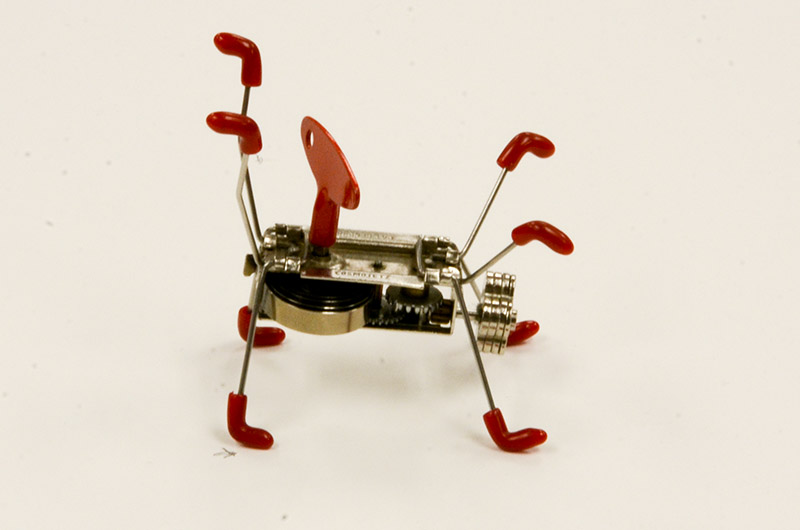

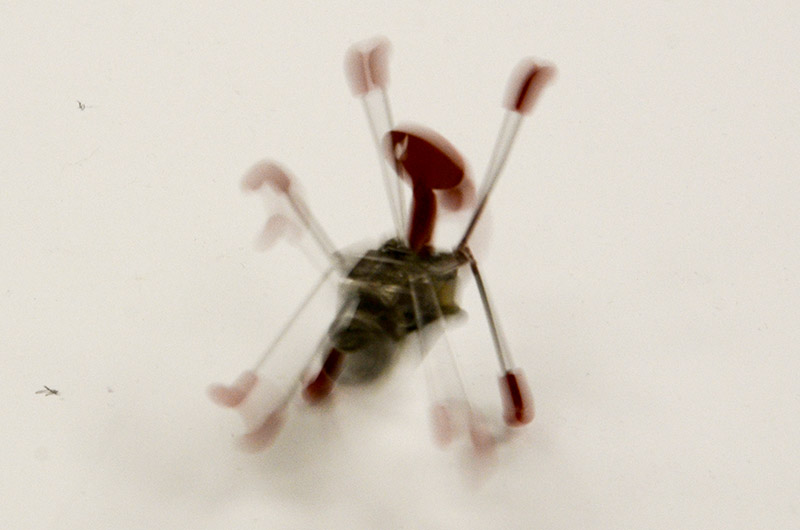

Here’s what our friend Cosmojetz looks like when we wind it up and let it go:

At the low end of the “average” range, a 1/60 shutter with a subject this rapid produces a lot of blur. Still, you can at least make out the general shape. And all that motion blur gives the photo a strong sense of movement.

Nikon D7000, 92mm (28-200mm), 1/60, F/10, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

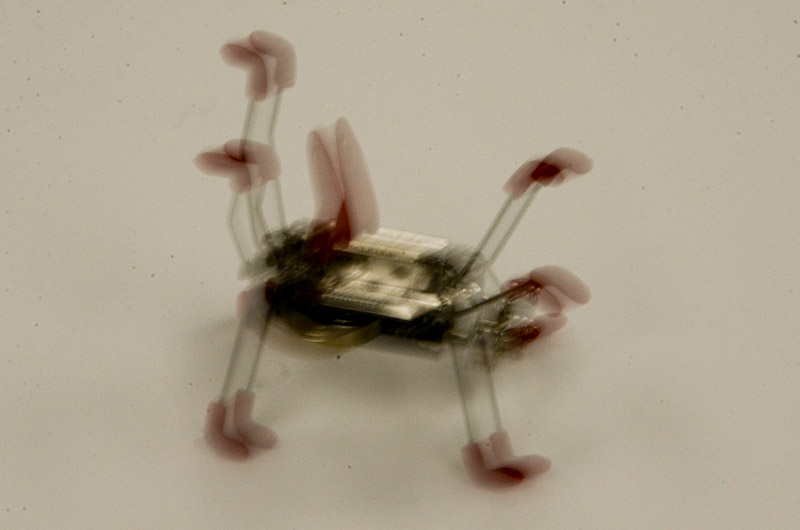

Just a little slower – 1/8 of a second – and our subject becomes an abstract study in motion, more blur than object at this point.

Nikon D7000, 92mm (28-200mm), 1/8, F/29, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

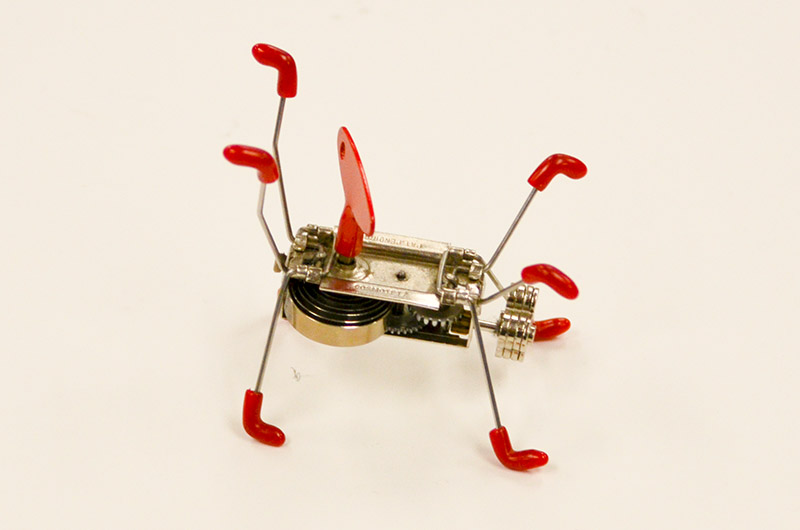

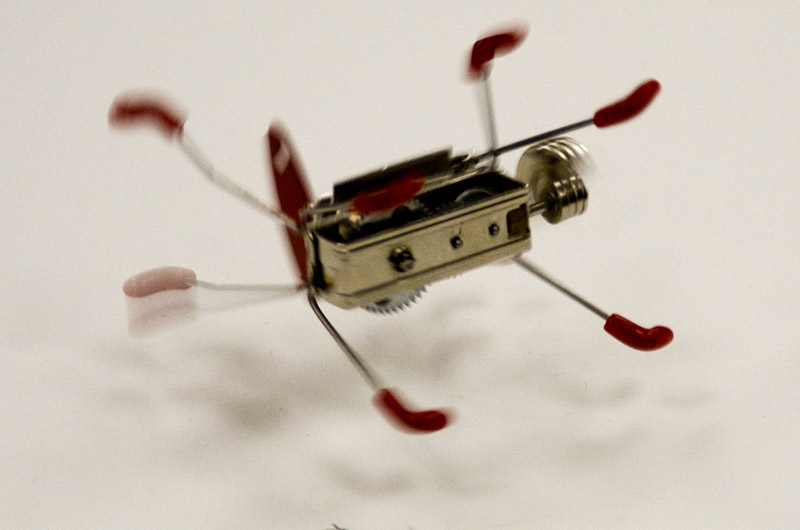

If we shift our shutter in the other direction – speeding it up – we can catch it in mid-bounce. Though there’s some motion blur to be found along the edges, the sense of movement here comes more from frozen motion. The subject is as clear as if it were standing still, but its tilted at an angle that indicates motion. The shadow also suggests that it’s either on the move or floating in space (and gravity generally prohibits floating in midair).

Nikon D7000, 92mm (28-200mm), 1/250, F/5.0, ISO 400, cropped and adjusted

For more examples of how shutter speed affects light and motion, have a look at these entries in The Photographer’s Sketchbook blog.

You’ll also find plenty of links to further information about shutter speed on the “Camera Controls” board on Pinterest.